A new analysis examines 177 countries’ ability to invest in health through 2027. Copyright: World Bank

A new analysis examines 177 countries’ ability to invest in health through 2027. Copyright: World Bank

In the 1980s and 90s, a convergence of factors including high debt burdens contributed to severe and prolonged weakening of health systems in some of the world’s poorest countries. Resource-starved health systems proved powerless to control the spread of HIV/AIDS, leading in the ensuing years to vast loss of life and squandered economic opportunity on a global scale.

Comparable forces are coming to bear on some of the world’s most fragile health systems in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis—but there’s still time for countries and their partners to avoid repeating the health financing errors made 40 years ago.

New wounds to vulnerable health systems

Finding better solutions amid current stresses won’t be simple. The health and economic double shock of COVID-19 has left deep scars in many countries, while Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has caused a new series of upheavals, disrupting supply chains and spurring price surges for energy, food, and other commodities.

Added to inflationary pressures that had already been building, these shocks are inflicting fresh wounds on vulnerable economies and health systems, widening global disparities, and placing goals like universal health coverage (UHC) at high risk.

A new update to our March 2021 paper, “From Double Shock to Double Recovery – Implications and Options for Health Financing in the Time of COVID-19,” analyzes the evolving macro-fiscal situation in 177 countries and assesses its likely impacts on health spending through 2027.

Subtitled “Old scars, new wounds,” the update argues that, by acting together now, countries can narrow global gaps in health spending capacities, bolster future pandemic preparedness, and prime health systems in all countries for inclusive health and economic recovery.

Rifts in country health spending capacities: wide and widening

Our analysis shows that today’s deteriorating macroeconomic situation will affect countries in markedly different ways. Forty-one countries face the prospect of lower per capita government spending in 2027 than in 2019 (pre-pandemic), tantamount to a lost decade for public investment.

In another 69 countries, government spending per capita will exceed 2019 levels through 2027, but spending growth will be weak, restricting countries’ capacities to boost public investment in critical areas such as health.

In only 61 of the 177 countries analyzed will the capacity of governments to spend increase robustly to 2027.

As these divergent trends play out, countries will be unequally positioned to tackle health challenges and manage their economic impacts, further widening disparities in a divided world. At one extreme are higher-income countries with already-strong health financing and whose government spending capacity is poised to grow robustly in the years ahead. At the other extreme are lower-income countries where health spending is historically weak relative to wealthier countries and whose government spending capacity is expected to languish or lose ground.

And of great concern are four low-income countries (LICs) and 14 lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) that are expected to see their government spending capacity lag below pre-COVID-19 levels through 2027. In addition, another 10 LICs and 19 LMICs will see very slow growth in government capacity to spend, including on health.

Interest on public debt bites into health investments

Adding to these trends are the pressures from public debt, which complicate the health financing picture for many countries. Public debt had risen before COVID-19 hit, and countries borrowed to meet pandemic needs. As central banks continue to raise interest rates to control inflation, debt distress will grow.

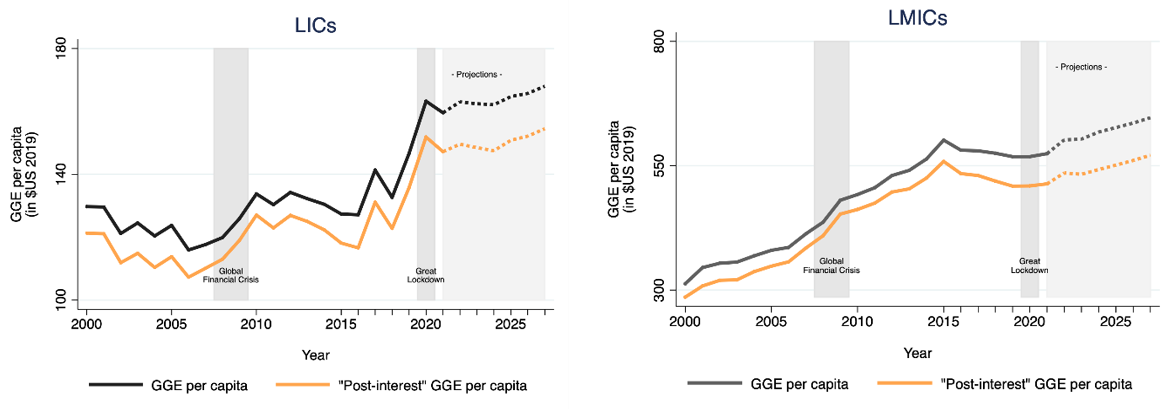

Higher interest payments on public debt are already limiting governments’ capacity to spend, including on health (Figure 1). These pressures affect countries differently across income groups and spending prospects.

Unfortunately, the effects will be most devastating in countries whose health spending options are starkly limited. In low-income countries, interest payments are expected to constrain the capacity to spend on health on average by 7 percent and in lower middle-income countries by 9 percent in 2027. The impact varies vastly across these countries, in some of them, they are expected to constrain their health spending capacity between 15-30 percent in 2027.

Immediate action can check wider deterioration

Today, scores of vulnerable countries face stark constraints in their capacity to spend on health, and the shrinkage or stagnation in their spending capacities may signal the start of a broader deterioration in health spending and subsequent economic growth. Without immediate action, new wounds atop old scars in health systems mean that some countries will be left behind on the path to health and economic recovery.

Some of the important levers for action are in the affected countries’ own hands. Urgent domestic policy responses include increasing government revenues as a share of GDP through improved fiscal policies and their enforcement, boosting the priority given to health in budgets, and improving the efficiency and equity of spending.

However, in many of the settings where robust, sustained investment in health systems is most urgently needed, domestic efforts alone will not be enough. This was also the case in the 1980s. At that time, many debt-stressed countries, under pressure from creditors, slashed their government health budgets. As health systems deteriorated, HIV/AIDS brought the reckoning, and vulnerable people paid the price.

The global community can avoid replaying such scenarios in the aftermath of COVID-19. By recognizing joint interests and backing that recognition with resources and actions, such as external financing and debt relief, high-income countries today can contribute to bolstering health spending capacities in the fragile health systems where those investments will do the greatest good. In the process, rich countries will reinforce their own health and economic security. As COVID-19 lingers and new epidemics loom, ill-prepared health systems in vulnerable countries raise health risks and constrain economic opportunities far beyond those nations’ borders.

Forty years ago, debt-stressed countries and their partners navigated in largely uncharted waters. This time around, that’s not the case. As they work to end COVID-19, prepare for future pandemics, and reignite progress toward UHC, decision-makers can draw lessons from global health history, showing that collaboration is the surest form of self-protection. Countries are not doomed to relive the bad old days. But to reach better days, they need to elevate common interests and work together.

Join the Conversation