Improving employment outcomes for Colombian workers calls for a jobs strategy that addresses both the supply and demand sides of the labor market. Copyright: Shutterstock

Improving employment outcomes for Colombian workers calls for a jobs strategy that addresses both the supply and demand sides of the labor market. Copyright: Shutterstock

Education is often considered a pathway to better jobs. In Colombia, workers who have completed secondary education earn almost 30 percent more than workers with only a primary education, are 1.5 times more likely to have a waged job, and twice as likely to be covered by social security. By this account alone, the fact that the share of the working-age population with secondary education or above has risen from 42 percent in 2009 to 56 percent in 2019 should bode well for Colombia. But evidence from the Colombia Jobs Diagnostic report points to continued high labor market vulnerability for both low-educated and high-educated workers.

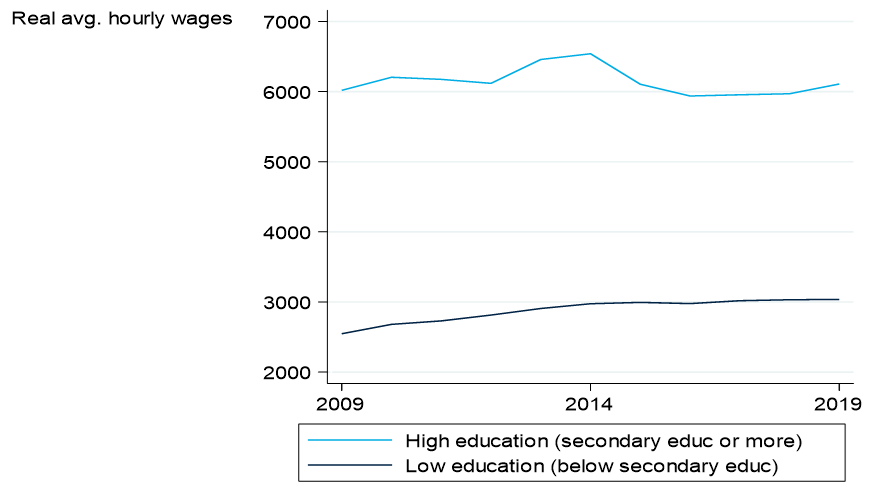

With the slowdown in economic growth since 2014, prospects for new graduates with secondary degrees or above have deteriorated. Between 2009 and 2014 average wages for high-educated workers (completed secondary education or above) rose by close to 9 percent before dropping by 7 percent between 2014 and 2019 (Figure 1). The unemployment rate followed a similar trend, displaying first a decline during the first half of the decade followed by an increase in the second half (Figure 2). New graduates with higher levels of education were a key contributing group to the latter increase in unemployment. The share of high-educated workers among the unemployed rose from 63 to 69 percent between 2014 and 2019, as the demand for skilled labor slowed.

Figure 1: Real average hourly wages

Figure 2: Unemployment rate, disaggregated by education level

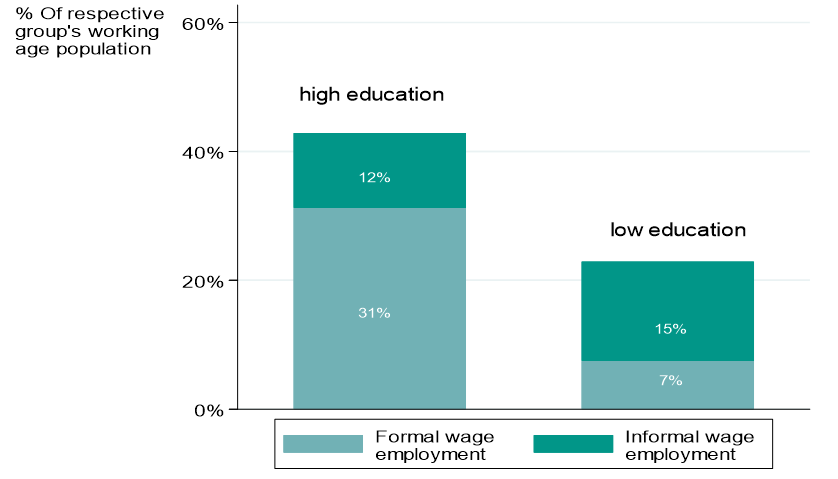

For less educated workers—still a large share of the working-age population—the challenge is arguably different. Real average hourly wages for workers with less than secondary education continued to rise despite the economic slowdown (Figure 1), and 2019 unemployment rates were lower among workers with less than secondary education than among workers with secondary education or above (8.6 versus 12.7 percent). Yet, less-educated workers find it much harder to secure “good” jobs compared to educated workers. In 2019, only 23 percent of the working-age population with less than secondary education held waged jobs and only 7 percent had formal waged jobs (with contract and social security), compared to 31 and 12 percent for the more educated workers (Figure 3).

Colombia’s premature shift from manufacturing towards services sectors could be one of the reasons why wage employment opportunities for the less-educated workers are so scarce. But the evolution of private sector employment points to more general substitution of less educated workers as the share of wage employees with less than secondary education has been falling across all main sectors of the economy over the last decade (Figure 4). Unable to afford unemployment or benefit from the increasing number of jobs in high value-added services sectors, less-educated workers are often pushed into self-employment, which is less formal, pays less, and is more insecure.

Figure 3: Wage employment for high- and low-educated workers, disaggregated by contractual status

Figure 4: Low-educated wage employment by economic sector

On the supply side, skills development should be better aligned with the need of the productive sectors and with workers’ profiles. The Job Diagnostic for Colombia suggests three areas of improvement for the training policy to work, namely:

- Implement a targeted strategy for informal workers, low-educated workers, and the unemployed and inactive population to link them to training that improves their employability.

- Make trainings more relevant using information from the vacancy databases collected by the Public Employment Service (SPE in Spanish), which could be complemented by regional consultation groups with the private sector.

- Take stock of the training courses and regulate their offering through the network of SPE providers.

On the demand side, as Colombia works on a transition to high-productivity services, the policy focus should be on managing effects of the structural shift away from manufacturing. This will require increasing the competitiveness of Colombian products, improving the productivity of the agricultural sector, and minimizing distortive minimum wage and labor costs. These factors have harmed the performance of manufacturing industries, contributed to an excess of labor supply relative to demand in urban areas, and incentivized more capital-intensive production, pushing workers—particularly the less educated—towards lower-productivity and lower-quality jobs.

This is the second blog in a series based on the World Bank Group’s report, Colombia Jobs Diagnostic: Colombia’s Structural Challenges for the Creation of More and Better Jobs. Our next blog will examine Colombia’s urban-rural employment duality, characterized by an agglomeration of jobs in low-productivity services in its cities, and a structural deficit of wage employment outside them.

Join the Conversation