[Also available in Japanese]

Globally, up to 1.4 million people are moving into urban areas per week, and estimates show that nearly 1 billion new dwelling units will be built by 2050 to support this growing population. The way we build our cities today directly impacts the safety of future generations.

So how do we ensure that we are building healthy, safe, and resilient cities?

Building codes and regulations continue to be among the most cost-effective tools, and can be seen in Japan’s effective use of building regulations to reduce risk.

Today, Japan has a well-established and robust building regulatory framework. But this was not how it began. Japan first initiated its building regulatory reform under conditions similar to those in many low- and middle-income countries: limited technical and institutional capacity, poor construction quality, and high demand for affordable housing.

How effective are building regulations in reducing disaster risk?

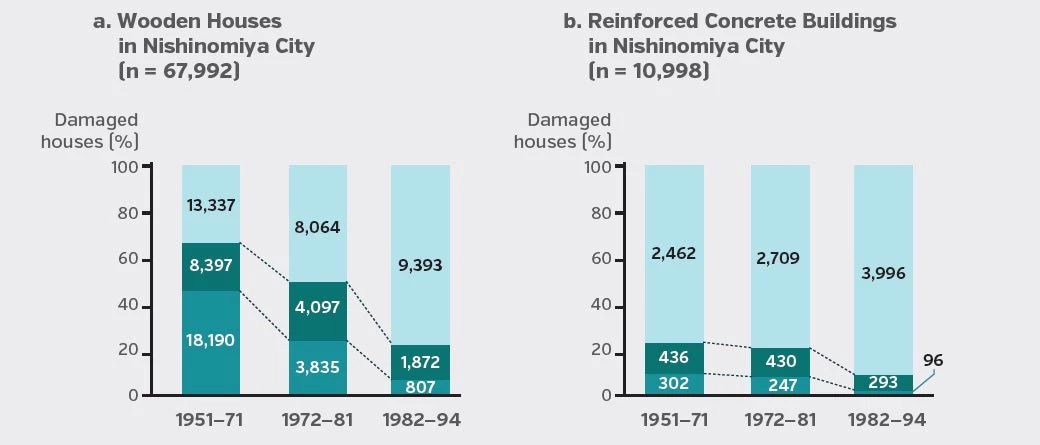

The new seismic code was put to the test in 1995, when the devastating Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake struck the southern Hyogo Prefecture, causing 6,437 deaths and destroying approximately 100,000 houses. Damage assessment data showed the remarkable risk-reduction impact of improved building regulations. Buildings constructed to the 1981 standards performed significantly better in the earthquake, accounting for just 3 percent of collapsed buildings.

Following the earthquake, there was significant political momentum to increase building code compliance and promote seismic retrofitting to improve structural safety by the modification of existing structures. As of 2013, 82 percent of residential buildings were earthquake-resilient. The country aims to achieve 95 percent seismic resilience by 2020.

A new World Bank report, “ Converting Disaster Experience into a Safer Built Environment: The Case of Japan,” captures how the country has incrementally improved building regulation and strengthened enforcement mechanisms. Developed in partnership with the Japanese Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT), and Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR), the report plots Japan’s journey of regulatory reforms pertaining to building construction from the 19th century to today.

Fortunately, improvements in building sciences, institutional processes, knowledge resources, information and communication technology solutions, and other technologies can enable similar reforms to take place over a much shorter time scale in low- and middle-income countries.

Key takeaways from the report include the following:

- Education, advice, and financial incentives can be an effective way of creating an enabling environment for compliance. Japan has introduced training and licensing of building professionals and set up loan programs offering tax breaks and other incentives for houses that exceed the mandatory minimum standard of safety.

- Increasing local enforcement capacity through collaboration with the private sector. Since 1998, local governments have allowed designated private sector bodies to carry out design confirmation and construction inspection. To mitigate associated risks, they have established mechanisms for oversight, fairness, and conflict resolution.

- Formal regulatory systems should recognize prevalent construction practices including nonengineered construction. In Japan, wooden housing structures are common. Over time, these conventional and originally low-strength structures with little or no application of engineering knowledge have become safer and more earthquake-resilient because of the gradual improvement of building-science research and large-scale education efforts. The national building code includes standards for wooden structures, and the government has invested resources to train carpenters and engineers who specialize in wooden construction.

The World Bank’s Building Regulation for Resilience Program (BRR), supported by the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) and its Tokyo Disaster Risk Management Hub, helps low- and middle-income countries strengthen the resilience of their built environments through the implementation of effective building and land-use regulations. The BRR Program also supports the promotion of other urban and social development objectives such as climate change adaptation and mitigation, accessible and inclusive urban development, and cultural heritage protection and restoration.

The BRR Program can deploy the tools, resources, and expertise of more than a dozen international partner organizations that are active in regulatory capacity assessment, building standards, building quality assurance, green building code development and certification, legal reform, and training of regulatory personnel and informal builders.

In the context of rapid urban expansion, strengthening and implementing building regulations can play a significant role in ensuring safe, healthy and resilient construction practices. The BRR Program will continue to support countries in furthering this agenda.

Related:

- Report: Converting Disaster Experience into a Safer Built Environment: The Case of Japan

- Blog post: Making homes safer to build resilient cities

- Subscribe to our Sustainable Communities newsletter and Flipboard magazine

- Follow @WBG_Cities on Twitter

Join the Conversation