Yes, there are approximately 65 million refugees, asylum-seekers and internally displaced people worldwide. Yes, conflicts continue unabated, producing inordinate human misery. Yes, we urgently need political solutions.

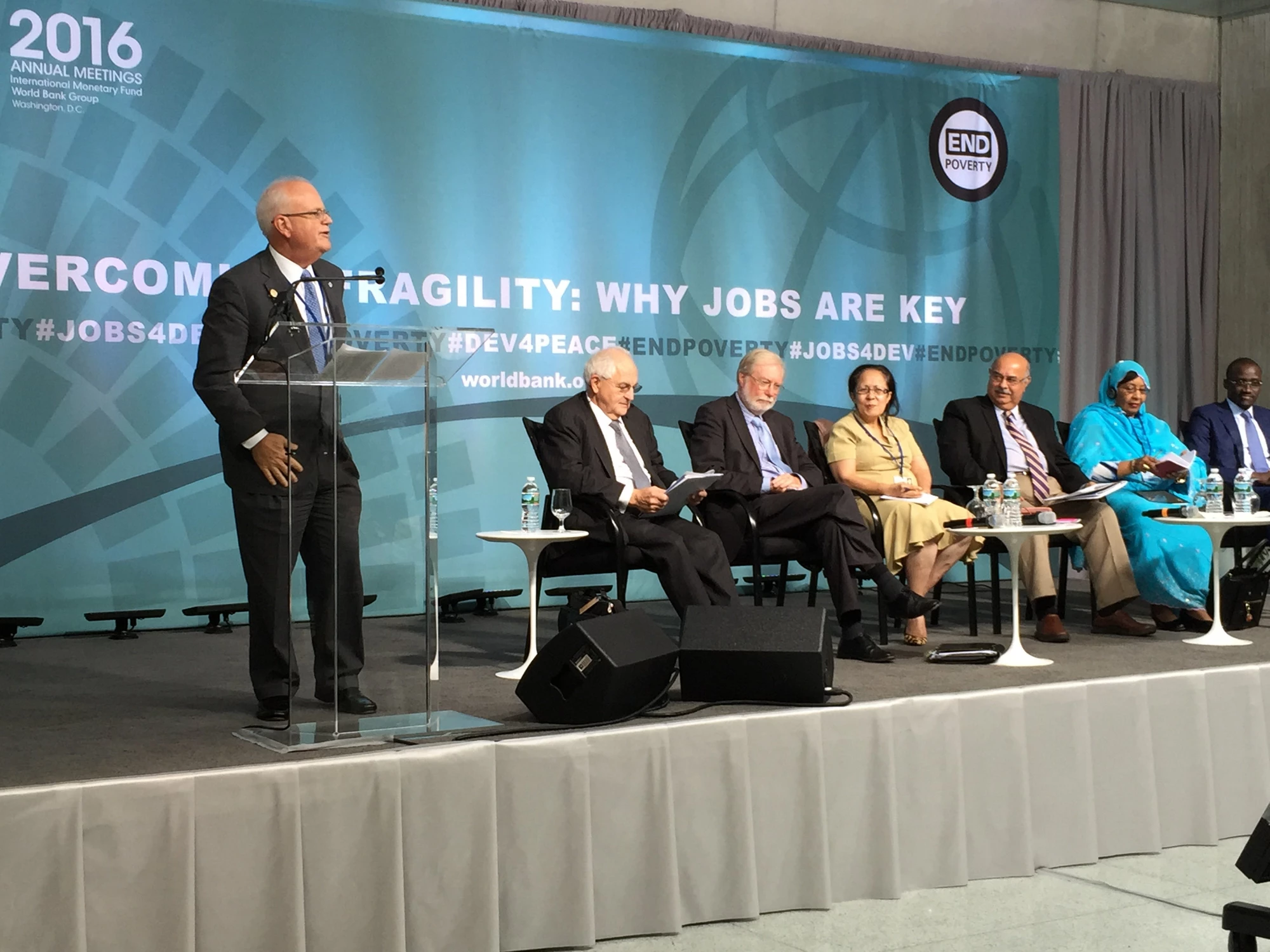

But there is growing consensus that creating jobs so people can work—wherever they are—is key to escaping fragility and preventing further conflict. And it’s what we need to focus on right now, experts and policymakers agreed at the “Overcoming Fragility: Why Jobs Are Key” event on Friday during the World Bank-IMF Annual Meetings in Washington, DC.

World Bank interim Chief Operating Officer and Managing Director Kyle Peters opened the event saying the world will need half a billion jobs by 2030.

“To make sure that young people entering the job market have a chance to build a life for themselves, fragile and conflict affected states—alone—will have to add five million new jobs each year for the next 15 years,” Peters said. “Development happens through jobs.”

Peters said the Bank Group is proposing that shareholders approve $2.5 billion in support to the private sector in the poorest countries—especially those affected by conflict or considered fragile.

It’s the “miracle of productivity,” which lifts people out of poverty and fragility, said Paul Collier author of The Bottom Billion and professor of economics and public policy at the University of Oxford. Public money should go toward “encouraging decent firms to go where they are desperately needed” so jobs can be created. Public investment to enable firms to become productive should complement investment in health, education and basic infrastructure.

“Jobs are fundamental in order to prevent the alternatives,” said Stefano Manservisi, director general, of International Cooperation and Development at the European Commission. Manservisi described the EU’s support of job creation in sub-Saharan Africa, which combats terrorism and reduces the flow of migration into Europe, he said.

Three policymakers on the panel offered hope, sharing experiences in creating jobs amid fragility.

Former Minister of Finance in Timor Leste Emilia Pires described the government’s decision to put money directly into the hands of the country’s internally displaced people—15% of the population in 2006. It was a risk, she said but people used the cash grants to start their own small businesses which, in turn, helped bring peace and stability to the country.

Since 2012 reforms in Cote D’Ivoire have focused on attracting investment and improving education to create jobs, said the Minister of Budget Abdourahmane Cissé. Major reforms to the business environment slashed the time and money it takes to start a new business, he said. The government also raised the minimum price of cocoa beans, which increased farmer revenues and created more agricultural jobs. Five new public universities will be built by 2020, Cissé said.

“I would rather have people in my country who are educated and can’t find jobs, than people who are uneducated—because they will never find jobs,” said Cissé.

Arif Nadeem, CEO of the Pakistan Agricultural Coalition, described efforts to create jobs by cultivating cotton in the poorest regions of Pakistan, where terrorist organization recruitment is rife. His organization brings top-notch agricultural technology providers to Pakistan to help farmers and connects farmers to financing and markets.

The focus on agriculture was echoed by Mariam Mahamat Nour, the Minister of Economy and Planning for the Republic of Chad, a country with about 480,000 forcibly displaced persons. “It’s essential to find sustainable solutions for the livelihoods of displaced people,” Nour said, “Sustainable employment passes through agriculture—there are both skilled and unskilled jobs there to tackle the challenge.”

Moderator Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator for the Financial Times ended the event with a mix of concern and hope. “We are grotesquely misallocating resources in dealing with people in conflict,” he said referring to the need for more public investment in helping to create jobs.

But he also pointed to the success of Korea, a country which emerged from war in the 1950s to become an economic powerhouse today. “It is possible to come out of these situations,” Wolf said.

Related:

Join the Conversation