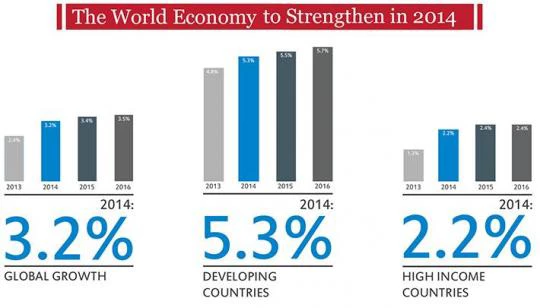

The global economy is finally emerging from the financial crisis. Worldwide, growth came in at an estimated 2.4 percent in 2013, and is expected to rise to 3.2 percent this year. This improvement is due in no small part to better performance by high-income countries. Advanced economies are expected to record 1.3 percent growth for the year just finished, and then expand by 2.2 percent in 2014. Meanwhile, developing countries will likely grow by 5.3 percent this year, an increase from estimated growth of 4.8 percent in 2013.

The world economy can be seen as a two-engine plane that was flying for close to six years on one engine: the developing world. Finally, another engine – high-income countries – has gone from stalled to shifting into gear. This turnaround, detailed in the World Bank’s Global Economic Prospects 2014 launched last Tuesday, means that developing countries no longer serve as the main engine driving the world economy. While the boom days of the mid-2000s may have passed, growth in the emerging world remains well above historical averages.

High-income countries continue to face significant challenges, but the outlook has brightened. Several advanced economies still have large deficits, but a number of them have adopted long-term strategies to bring them under control without choking off growth.

There is also guarded optimism about the Euro Zone, where growth rebounded in the middle of 2013, and will likely expand by 1.1 percent in 2014 after two years of recession. Given Europe's difficulties over the past six years, even modest growth provides a sense of hope. In the United States, despite a disappointing employment report for December, the vast majority of economic data look strong, and we expect growth to jump from 1.8 percent in 2013 to 2.8 percent this year.

Yet, several countries remain vulnerable. Unemployment in southern Europe remains concerning, particularly the percentage of highly educated young people who can’t find good jobs. In the developing world, accelerating poverty reduction will require governments to adopt structural reforms that promote job creation, boost investment in infrastructure, strengthen financial systems, and shore up social safety nets for the poor.

Adding to these concerns, the decision by the U.S. Federal Reserve to taper its monetary stimulus poses significant risks for developing countries. We saw this past summer that even the fear of the taper spooked markets and caused investors to pull capital out of emerging economies. Fortunately, the Fed’s recent announcement hasn’t led to a similar market reaction to date, but capital flows to emerging markets could still become more volatile going forward.

The most likely scenario remains encouraging: A smooth and modest tapering, with capital flows to developing countries decreasing gradually and growth and financial stability remaining broadly stable. Our downside scenario, which is much less likely, suggests that if long-term U.S. interest rates jump quickly, then capital flows could fall by 50 percent or more for several months.

The extent to which the taper affects capital flows to developing countries depends to a large degree on the kind of capital flows they receive. For instance, foreign direct investment will likely prove less sensitive to the taper than bonds or equities. Importantly, most capital flowing into China comes in the form of foreign investment. As a result, China is less sensitive to our taper scenarios. Domestic factors will also have a significant bearing on how hard countries are hit, which is why developing countries need to move quickly to adopt reforms that will reduce economic imbalances and financial vulnerabilities.

It’s also worth pointing to the bright spots highlighted in our Global Economic Prospects report. Despite the tragic and ongoing flare-ups in South Sudan and the Central African Republic, Sub-Saharan Africa as a whole represents one of the world’s most promising economic stories. Overall, the region grew by 4.7 percent in 2013, and we expect growth to accelerate to 5.3 percent in 2014.

The continent’s demographic structure is also evolving in a way that will likely encourage strong growth going forward, as more young people are entering the workforce and boosting potential output. Capital inflows have also ticked-up, as governments improve their business climates. Generally speaking, the forecast for Africa looks good.

So, for now, when I look at the outlook for the global economy, I see cause for optimism. My hope is that the policymakers charged with driving and sustaining global economic prosperity have taken on-board the hard lessons learned from six years of weathering extreme turbulence.

This post first appeared in LinkedIn Influencers.

(Photo Credit: bigbirdz/Flickr)

Join the Conversation