The just-released Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey (ALCS) paints a stark picture of the reality facing Afghanistan today. More than half the Afghan population lives below the national poverty line, indicating a sharp deterioration in welfare since 2011-12.[1] The release of these new ALCS figures is timely and important . These figures are the first estimates of the welfare of the Afghan people since the transition of security responsibilities from international troops to the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) in 2014.

While stark, the findings are not a surprise

Given what Afghanistan has gone through in the last five years, the significant increase in poverty over this period is not unexpected. The high poverty rates represent the combined effect of stagnating economic growth, increasing demographic pressures, and a deteriorating security situation in the context of an already impoverished economy and society where human capital and livelihoods have been eroded by decades of conflict and instability.

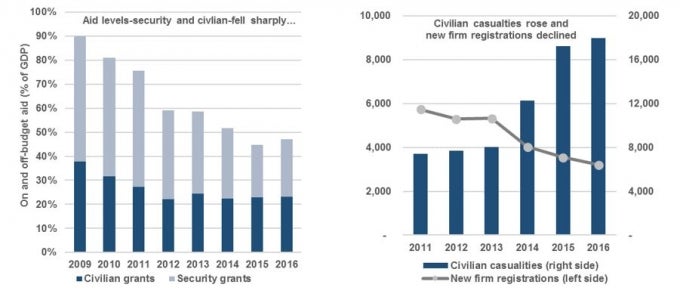

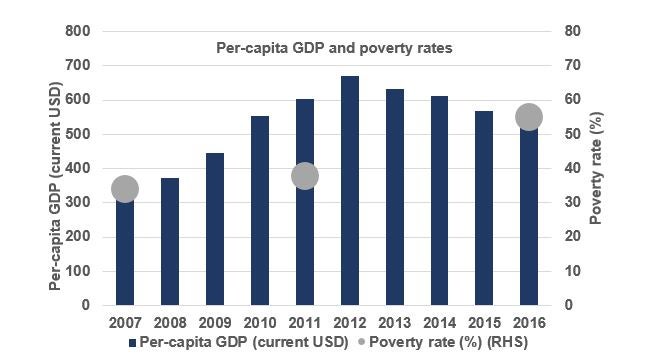

The withdrawal of international troops starting in 2012, and the associated decline in aid, both security and civilian, led to a sharp decline in domestic demand and much lower levels of economic activity. The deterioration in security since 2012, which drove down consumer and investor confidence, magnified this economic shock. Not surprisingly, Afghanistan’s average annual rate of economic growth fell from 9.4 percent in the period 2003-2012 to only 2.1 percent between 2013 and 2016. With the population continuing to grow more than 3 percent a year, per capita GDP has steadily declined since 2012, and in 2016 stood $100 below its 2012 level. Even during Afghanistan’s years of high economic growth, poverty rates failed to drop, as growth was not pro-poor . In recent years, as population growth outstripped economic growth, an increase in poverty was inevitable.

Population movements linked to security concerns have reinforced the downward trend. Since 2014, growing insecurity has led to mass internal displacement . Meanwhile, in 2016 alone, more than a million Afghans who had previously sought refuge in neighboring countries, returned to Afghanistan. In an already difficult context, this large-scale internal displacement and massive return has put added pressure on the delivery of public services and increased competition for scarce economic opportunities, not only for the displaced, but for the population at large.

These welfare trends reflect an emerging humanitarian crisis, aggravated by rising food insecurity and a stagnating labor market. Mirroring the increase in poverty, food insecurity has climbed from 30 percent in 2011-2012 to 45 percent in 2016-2017. More than four out of five Afghan adults (ages 25 and above) have not completed any level of education. A quarter of the labor force is unemployed, and 80 percent of employment is vulnerable and insecure . With half the population below the age of 15, each year, large numbers of young Afghans continue to enter the labor market, most with little education and few productive employment opportunities. And as progress on education slows, the scale of the challenge will continue to grow.

An opportunity to act and signs of hope

These findings, while stark, are not a reason for despair, but a call to action. Despite the many challenges Afghanistan has faced since 2002, including what was an almost impossible situation in 2014, Afghanistan has made remarkable progress in many critical areas, and there are many fresh signs of hope.

While economic growth remains low, 2015 may have been a turning point . With solid economic management, growth rates have picked up since then, and business confidence appears to be slowly recovering. Given Afghanistan’s natural endowments and strategic location, the potential for growth to accelerate even further is there if the right policies and programs are implemented.

Despite ongoing insecurity, primary healthcare access is expanding to remote, rural communities , thanks to innovative forms of collaboration between government and civil society, and the dedication and courage of frontline service providers. Since 2003, the health of Afghans has steadily improved. The number of children dying before their 5th birthday dropped by more than a third between 2003-2015. Rates of childhood stunting—or low height for their age—have declined by 2 percent a year, faster than a global median of 1.3 percent a year in comparable countries. Such success can spread to other fields.

Afghanistan’s youth represent another source of hope as do Afghan women . With the right skills and opportunities, young Afghans have the potential to sow the seeds of positive change and become a dynamic source of innovation, entrepreneurship, growth, and social progress for their country. And the economic empowerment of Afghan women has the potential to unleash as yet untapped sources of economic growth . Similarly, returning refugees can be a potent resource for Afghanistan’s future, if their skills can be nurtured and harnessed .

Maintaining confidence in the state’s ability to deliver core services—primary healthcare, basic education and skills, water and sanitation, transport connectivity, and law and order—for its citizens will be essential to building the durable peace needed to unlock Afghanistan’s potential. And to foster the inclusive growth that will be needed to reduce poverty, government policies, programs, and public investments must be focused on catalyzing private investment and job creation, helping entrepreneurs to get started, and for private businesses, small and large, to grow and create jobs.

What needs to be done is clear and the needs are many. The challenge lies in how all partners-—the government of Afghanistan, civil society organizations, private businesses, communities, and Afghanistan’s international partners—work together, to coordinate efforts, reduce fragmentation, focus on the timeliness and quality of implementation and on ensuring value-for-money. The ALCS results are a wake-up call and an opportunity we cannot afford to miss .

Join the Conversation