By now most of us have experienced firsthand how the new coronavirus, COVID-19, impacts our lives – our ability to leave home, work, go to school, or access public services. And yet, these impacts are not the same for everyone. Previous epidemics, such as HIV-AIDS, SARS, H1N1, and Ebola, have shown that the most vulnerable – be they countries, communities, households or individuals – often bear the heaviest burden. We want to bring attention to one such group: women and girls.

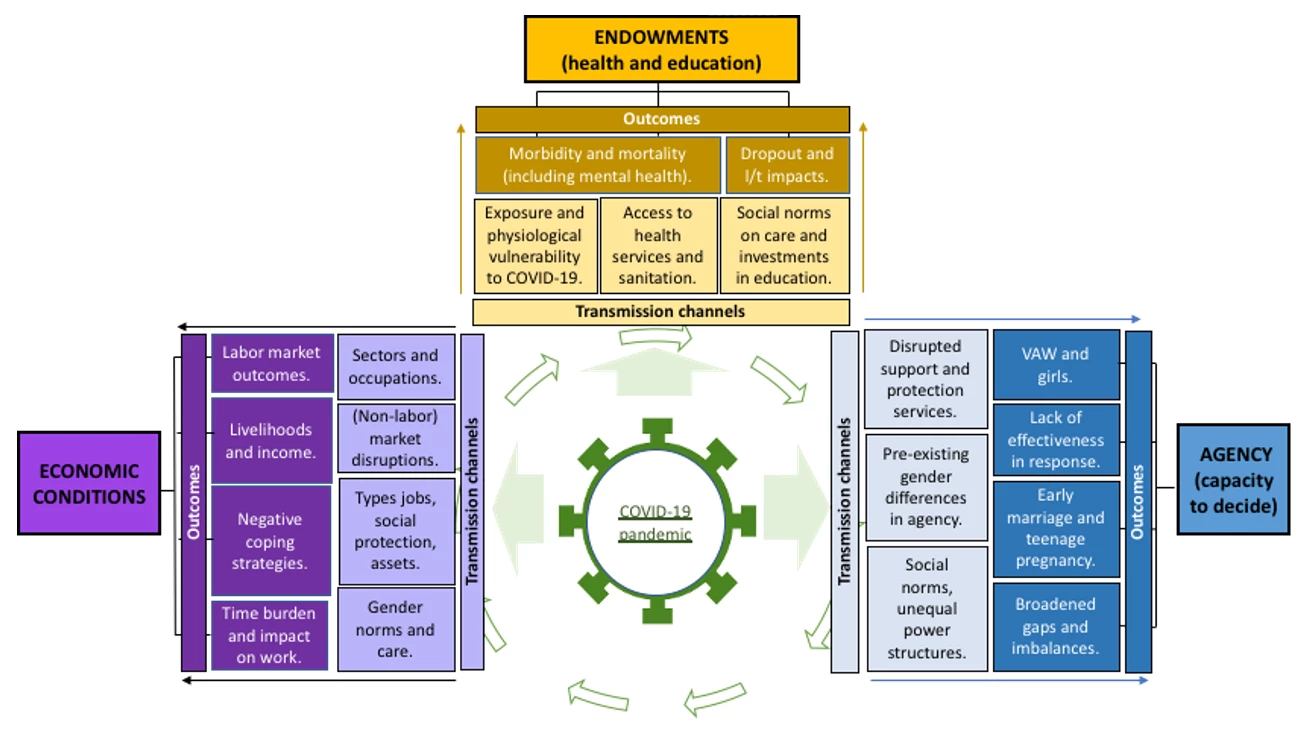

Pre-existing gender gaps may intensify the adverse effects of COVID-19. In fact, there is a high risk that gender inequalities will widen during and after the pandemic and that gains in women’s and girls’ accumulation of human capital, economic empowerment, and voice and agency, painstakingly built over the past decades, will be reversed. To formulate policies that are not gender-blind, it is important to understand the different ways that the COVID-19 pandemic and accompanying economic crisis may affect gender equality outcomes. These are illustrated in Figure 1 for the three focus areas of the World Bank Group’s Gender Strategy – economic conditions, endowments (health and education), and agency.

Figure 1: How COVID-19 affects gender equality outcomes

First, let’s consider the economic impacts of COVID-19. Across the world, women and men work predominantly in different industries. Many of the service sector jobs that are hit hard by the current crisis are disproportionately female. Think about receptionists, housekeepers, flight attendants, restaurant service staff, hairdressers, domestic workers, etc. But some manufacturing jobs also have a high concentration of female workers. For example, about half the employed women in Bangladesh work in textile or ready-made-garment manufacturing. Already, millions of garments workers, mostly women, have been sent home without further pay due to COVID-19.

Another point to consider, particularly in low-income countries, is that many women work in informal jobs and are thus not covered by social protection plans, such as unemployment insurance. Higher male mortality from COVID-19 makes it even more imperative for women left behind to be able to access social protection or other income support for their families.

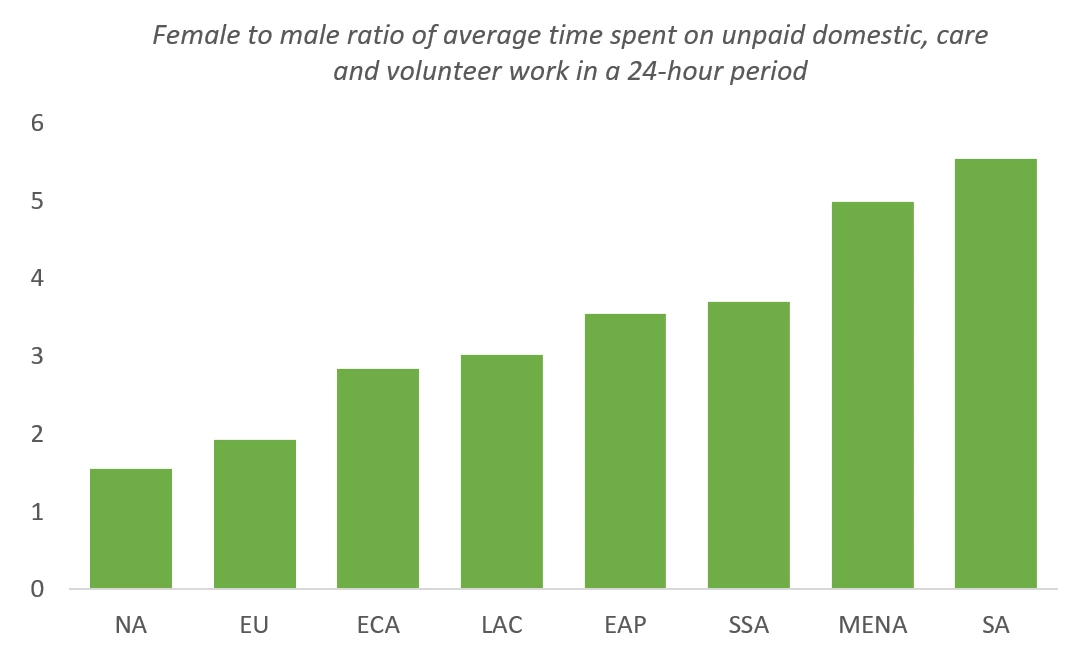

There is also the unequal distribution of care work between men and women within households. During normal times, women and girls bear the responsibility for household and family care due to social norms (see Figure 2). They will now most likely shoulder the increase in care demands brought about by the closure of schools, the confinement of elderly people, and the growing numbers of ill family members. There is a high risk that this will prompt many women worldwide to leave their jobs, especially those that cannot be performed remotely, with potentially long-lasting negative effects on female labor force participation.

Figure 2: Women carry the burden of care work

Let’s turn next to the health impacts of the crisis, which shows how COVID-19 can affect the endowments of men and women differently. By now it has been widely reported that men are at higher risk of dying from COVID-19 than women. The reasons are not fully understood, but evidence points to a combination of biological and behavioral factors. While this is a serious “male vulnerability,” women and girls also face specific health vulnerabilities during the current crisis.

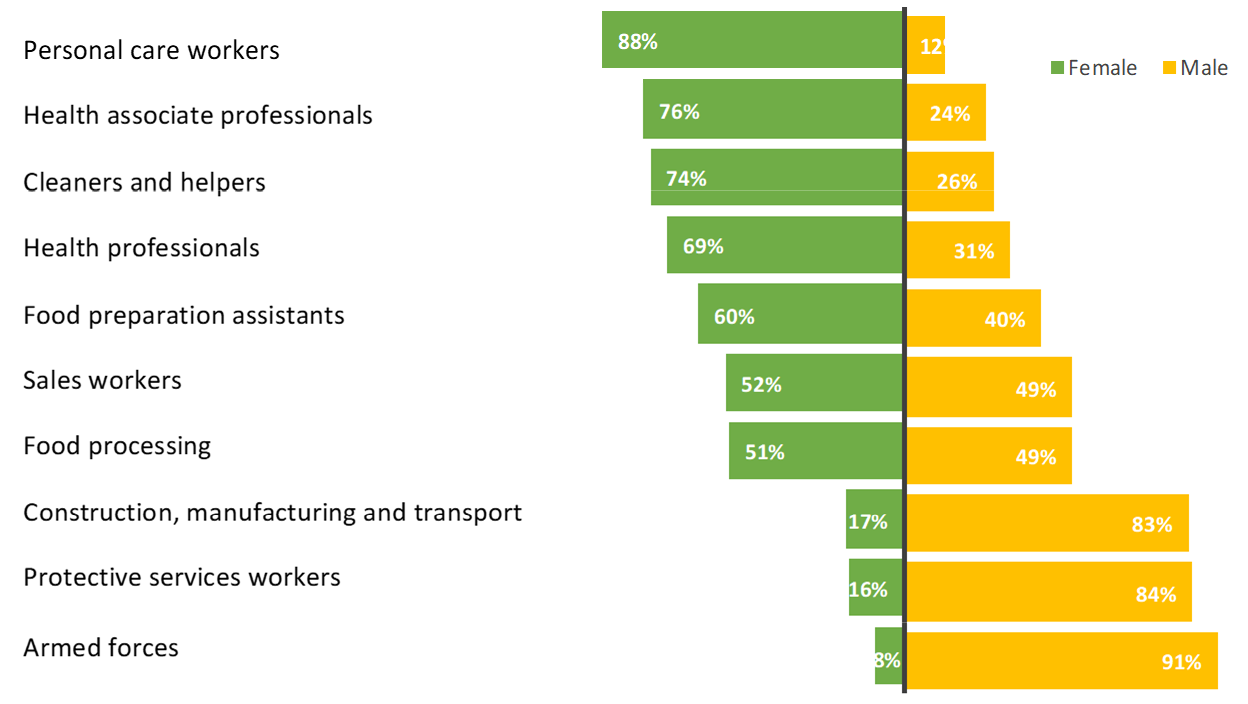

Due to their caregiving roles both inside and outside the home, women are disproportionately exposed to COVID-19. Globally, 88 percent of personal care workers and 69 percent of health professionals are female. These are frontline jobs that require patient contact and cannot be performed from home. In Spain, for instance, among infected health care workers, 71.8 percent are female compared to 28.2 percent male.

The shift of public resources toward the public health emergency can also pose a risk to sexual, reproductive, and maternal health services, particularly where health systems’ resources are highly constrained. During past Ebola and SARS crises, increases in maternal mortality were reported partly due to reduced access to health services and fear of contagion in maternity wards. Likewise, limits on access to reproductive health might increase unwanted pregnancies, particularly among adolescent girls.

Figure 3: More women than men work on the frontlines

And finally, women’s agency will likely suffer. One particularly egregious example is violence against women. Patriarchal norms, economic uncertainty and stress combined with confinement measures and disruptions in services have already triggered disturbing increases in domestic violence across countries affected by COVID-19, prompting the UN Secretary-General's urgent call to make the prevention and redress of violence against women a key part of national response plans (for example, including shelters as essential services, establishing warning systems with pharmacists and grocers, and ensuring that judicial systems continue to prosecute abusers).

What does that leave us with? We need to build an evidence base for policy making, by identifying the existing risks, generating high-frequency data on the gender impacts of COVID-19, and ensuring that policy responses and interventions respond to both males and females (we’ve summarized some of these recommendations in this document). Because the virus is not gender-blind, the response to it should not be either.

Join the Conversation