أطفال في اليمن أمام مبنى مدمر. anasalhajj / Shutterstock.com

أطفال في اليمن أمام مبنى مدمر. anasalhajj / Shutterstock.com

After the 2011 upheavals, countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) faced the reality of the flawed Social Contract that led to shattered relations between the State and its citizens. As countries consider their post-COVID policy options, here is another opportunity to rethink, re-engineer, and renew that contract, and build forward a better and more homogeneous society.

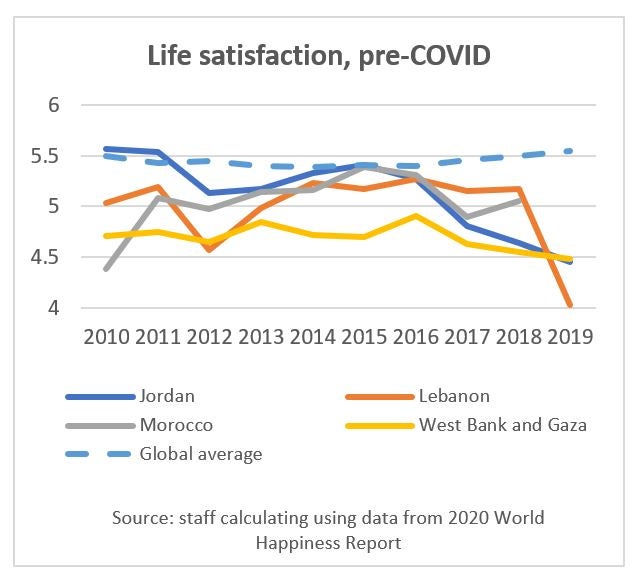

In the first blog in our series about how countries can navigate the COVID-19 pandemic, we argued that rising poverty, increasing life dissatisfaction, and deteriorating socio-economic outcomes make bold reforms a necessity in the MENA region. Declining life satisfaction unleashed social discontent in 2011, at a time when macroeconomic indicators were misleadingly reassuring. The alignment of less favorable development outcomes with even worse levels of life satisfaction and frustrations due to COVID create an even greater urgency for reform.

How should we go about this?

For an answer, we do not need to look far. A World Bank report published in 2018 argues that the key to understanding the upheaval of 2011 lies in the nature of the region’s Social Contracts:

The social contract between governments and citizens that had emerged since independence consisted of a questionable and unsustainable quid pro quo: the state’s providing jobs in the public sector, free education and health, and subsidized food and fuel to all citizens. In return, citizens were expected to keep their voices low and to tolerate some level of elite capture and political coercion.

Starting in the 2000s, that antiquated social contracts started to crack because persistent fiscal imbalances emerged. The fiscal burden of the system of general energy and food subsidies could no longer be sustained and had to be reformed. The public sector could no longer be the employer of choice and young people could no longer count on public employment after graduating from college. Impeded by distortions and elite capture, the private sector did not generate enough jobs to absorb the large number of young people entering the labor force. In addition, new generations came to adulthood; educated, open to the world and eager to participate in the public debate about public policies. As a result, the MENA region overall had some of the highest unemployment rates in the developing world, especially for youth and women. Moreover, while education and health care were free, and energy and water remained subsidized, the quality of these services was so poor that many people turned to the private sector for them. People felt that they needed connections to those in power to obtain good-quality jobs, and many expressed concerns that they could not move ahead no matter how hard they worked.

Because the social contracts were kept in place through coercion, and exclusion generated anger about relative deprivation between the connected and those without connections, a breakdown in the social contract increased the premium on freedom and created impetus for political change. (Pg. 12-13)

This abridged excerpt from the 2018 report describes the situation prior to 2011, but it also resonates for the present situation. Across the region, good jobs are hard to find, unemployment is unacceptably high, and many have opted out of the labor force altogether. Workers who remain active are primarily engaged in the informal sector. Service standards are inadequate with few signs of improvement, certainly not in the presence of COVID-19. Economic opportunities are limited, destitution is increasing, the business environment is poor, and there is no level playing field. Elite capture characterizes the economic sphere, which is dominated by public enterprises and private monopolies. It is little wonder that pent-up frustrations show-up as decreasing levels of life satisfaction. The Social Contract remains as antiquated as it was 10 years ago.

Three important lessons can be drawn from this analysis to inform our thinking on how the region can rebuild after COVID-19:

First, changing the Social Contract is as urgent as ever and needs to be taken up as countries are recovering from the pandemic. The previously mentioned report suggests where to start. It shows how life satisfaction is strongly associated with service quality, freedom to make life choices, perceptions of corruption, and economic well-being. Rethinking and renewing the Social Contract requires reducing corruption, increasing transparency, and above all, creating better and more inclusive economic opportunities.

Second, civil war does not lead to better outcomes. Nor does political revolution ensure improvements in the Social Contract. Enhancing civic participation in decision making would improve life satisfaction, but such changes are hard to bring about without the cooperation of entrenched interests who have the power to instigate instability. It is in the long term and sustained interest of all stakeholders, and most notably those in positions of power—whether political, economic or social—to open up and relax the way in for new generations of thinkers and entrepreneurs.

Third, incremental change in response to popular dissatisfaction is not an attractive alternative. Many MENA countries show declining life satisfaction to levels far lower than those found in 2010 (see graph). Few countries (e.g., Morocco) seem to be escaping this trend, suggesting there is something that can be learned from them.

As countries consider how to recover from COVID-19, they must do so in a way that improves their Social Contract. The poorly called “Arab Spring” yielded little success and did not improve the Social Contract. Even countries that responded with incremental reforms were largely unsuccessful. Post-COVID, countries need a more effective approach to improving the Social Contract. It requires walking a razor’s edge. Reforms need to be sufficiently fast to satisfy the region’s disgruntled citizens—mostly the youth among them—but change will need to be well designed, so that it does not run into resistance from powerful elites.

The World Bank stands ready to assist in building forward and better across the MENA region. We will continue to adopt a two-pronged approach: engaging the “fierce urgency of now” and planning the medium and longer term. For the immediate response, we are helping countries weather the crisis by providing short term financing and by investing in emergency projects in health and social protection, and with our IFC colleagues, moving to inject much needed financing into small and medium-sized enterprises to keep them afloat.

In the following blogs in this series, we will explore how win-win reforms can be designed that increase the productivity of the poorest and improve the quality of service provision. A focus on those at the bottom of the economic pyramid, data-driven decision making, digital transformation, and an effective bureaucracy are showcased to highlight reforms with the potential to improve the lives of the majority and to gain the political support to succeed.

This is the second in a series of blogs by Ferid Belhaj (Vice President for MENA) on what the World Bank can do to help navigate the COVID-19 pandemic and its socio-economic consequences. This blog is co-authored by Johannes Hoogeveen, Manager of the MENA Poverty and Equity Global Practice.

Join the Conversation