Des étudiants passent un examen au Caire, en Égypte, en mars 2021. (Shutterstock/Tamer Adel Soliman)

Des étudiants passent un examen au Caire, en Égypte, en mars 2021. (Shutterstock/Tamer Adel Soliman)

Last year, children in Saudi Arabia completed their classes virtually, and many have started their next grade in the same manner. As of the end of November, Saudi Arabia was among 9% of countries that relied solely on remote learning for primary school kids. The accessibility and ingenuity of e-learning has helped children continue their education. But it has been hard sometimes to collaborate with classmates or for younger students to get all their questions answered by the teacher in the online sessions.

Two thousand kilometers away, students in Egypt returned to in-person learning, under new protocols. They must wear masks at all times, and some activities aren’t allowed because of COVID risks. Students report that being in school is generally more fun but it’s been difficult to catch up on lessons, with about one-third receiving remedial help through tutoring (Economist).

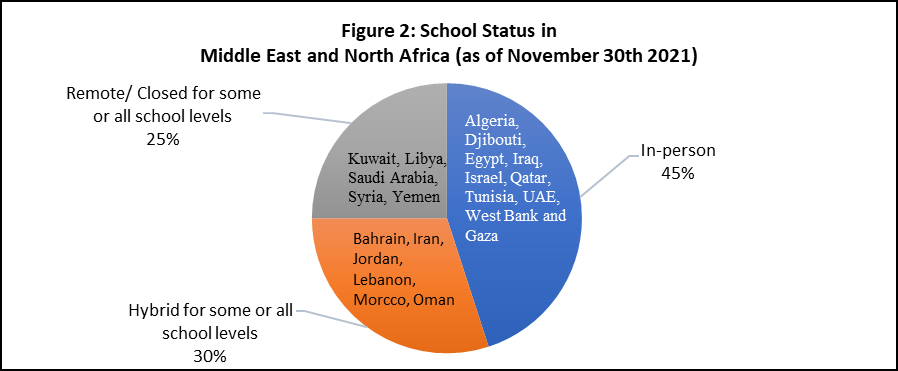

Across MENA, there is evidence that learning looks very different than it has in the past. While about half (45%) have returned to in-person, the remaining countries are relying on hybrid approaches or have kept schools closed at some levels or for some students (See figure 2).

|

|

Source: Global Education Recovery Tracker (GERT) and team analysis

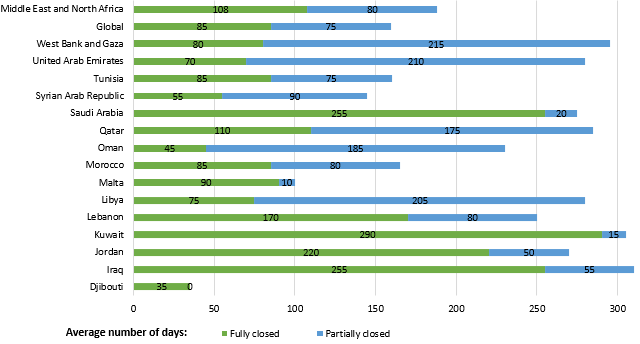

Almost two years of disruptions have affected over 110 million students across the region. On average, schools were fully closed for over 100 days with some students returning within a few weeks, while others continuing their education remotely for much longer, even until today (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3. School Closures across Middle East and North Africa (days)

Source: World Bank analysis of UNESCO Institute for Statistics data. |

Despite accessibility of remote learning during closures, students in MENA this year are academically behind cohorts of the same grades in previous years. A McKinsey global study of students’ progress at the end of the 2021 school year vs historical data shows significant “unfinished learning” in MENA. Similarly, the learning poverty rate, (proportion of 10 year-olds not able to read and understand a simple text) which was calculated at 63% in 2019, has likely increased to nearly 70% because of pandemic disruptions.(World Bank)

Equally disconcerting is the higher loss of opportunities for some vulnerable groups like girls in certain environments. While schooling translates to opportunities for all students, staying in school has a higher return on investment for girls (11%) than boys (7.3%) in the region. However, UNESCO estimates that nearly 500,000 girls in MENA may never return to school following the pandemic. This abrupt end to their studies brings a greater lifetime financial loss and higher risks of social disadvantages.

To help with recovery, the Bank and partners have stepped up efforts to support governments, largely helping ensure a safe return to teaching and learning. In Lebanon, the S2R2 Program is supporting the government in paying teaching staff subsidies. In Tunisia, the Strengthening Foundations for Learning Project is building a virtual online platform to expand teachers’ access to training and other development opportunities, with content that is sourced domestically and internationally. In Saudi Arabia, Bank technical assistance has supported the Ministry of Education in reviewing its digital and distance education experiences in response to the pandemic and to identify opportunities to harness the most effective new practices.

These efforts are crucial in a region where learning outcomes have been stagnant or in decline, as the recovery from COVID is all the more urgent. Sequencing of policies and interventions will be critical to success.

As a first measure, reopening schools and returning students to the classroom is paramount. To help guide countries, the World Bank, UNICEF, and UNESCO have partnered to establish guidelines for safe reopening. The prevalence of vaccines in some countries has enabled safe return to in-person education.

Second, it will be important to understand the extent of learning loss through rapid concise assessments . Using that data, governments can then tailor additional support, re-focus the curriculum, and adjust school calendars to maximize recovery impact.

Third, remedial support such as additional tutoring and other forms targeted at key groups (those at academic and economic disadvantage, those with special educational needs , and groups at higher risk of dropping out, and those who did not thrive in remote learning). While this is the most challenging approach, it is nonetheless timely and essential to close the gap on unfinished learning from recent years. Children will benefit more effectively from remedial support if it is targeted and meets them where-they-are in skill level.

Lastly, support should not be limited to students but extended to teachers as well . They are now operating in a new learning environment, with larger margins of learning levels and varying socio-emotional student needs. Conventional teacher training will likely not address the issues. In addition, coaching, mentoring, and establishing communities of practice for knowledge will need to move to the forefront of teacher professional development.

Join the Conversation