marine plastic

marine plastic

Jellyfish float eerily alongside plastic bags, schools of fish dodge plastic food packaging, and a lone manta ray skirts abandoned nets. These are the scenes of a viral 2018 video showing marine debris polluting the waters of Nusa Penida Bay in Bali, Indonesia, breaking the hearts of viewers across the world.

The video showed what happens when plastic production and consumption go unchecked. Indonesia has since taken actions to combat marine pollution, with the coordinating minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment (CMMAI), Luhut Pandjaitan, committing “Indonesia [to] embracing a sweeping, full-system-change approach to combatting plastic waste and pollution.” Spearheaded by CMMAI, Indonesia’s Plan of Action on Marine Plastic Debris (2017-2025) targeted a 70 percent reduction in marine plastic debris by 2025, aiming to control plastic pollution at its source. Of this target, the government has reported a 35.36 percent reduction of marine plastic debris as of December 2022.

Some of the efforts to help achieve the target included three World Bank-supported studies to inform policymaking and guide concrete actions on combating marine debris. These studies highlight the major sources of Indonesia’s marine plastic debris and provide policy recommendations for addressing the issue.

So, what did we learn from the studies about Indonesia’s marine plastic pollution?

First, abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing and aquaculture gear (ALDFG) and end-of-life fishing gear (EOLFG) are significant sources of marine debris.

Fishing gear like anchored gillnets, trammel nets, and plastic pots are at high risk of becoming ALDFG, polluting the marine environment. Without strong action to control this, over time this will lead to “ghost fishing,” where old/discarded fishing gear entraps marine animals.

Second, major rivers are important sources of marine plastic waste.

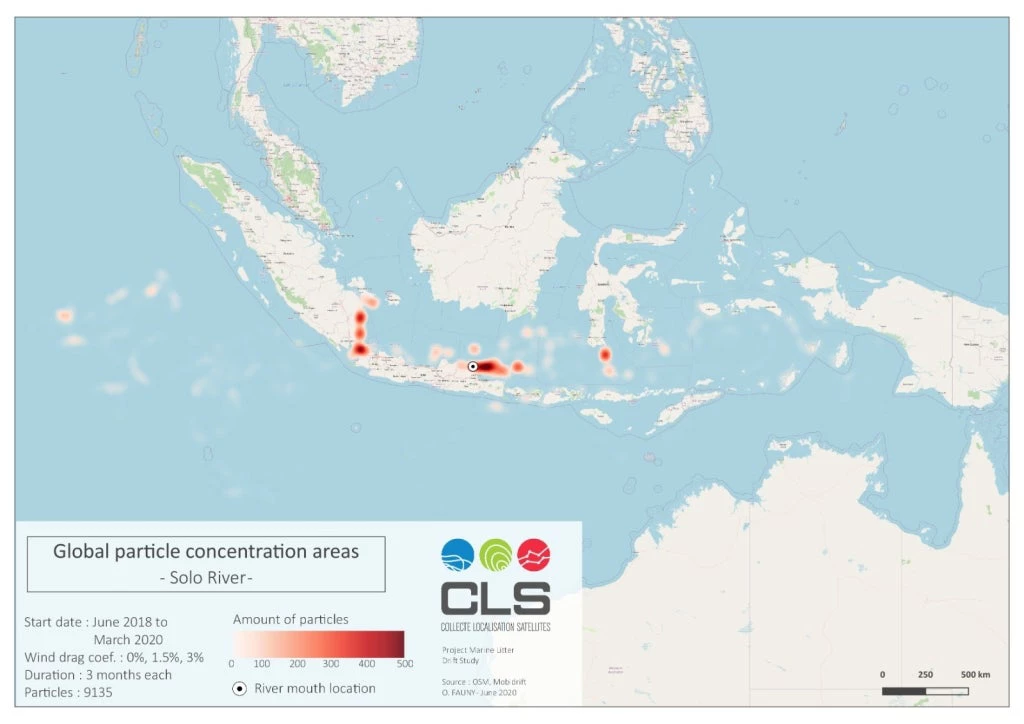

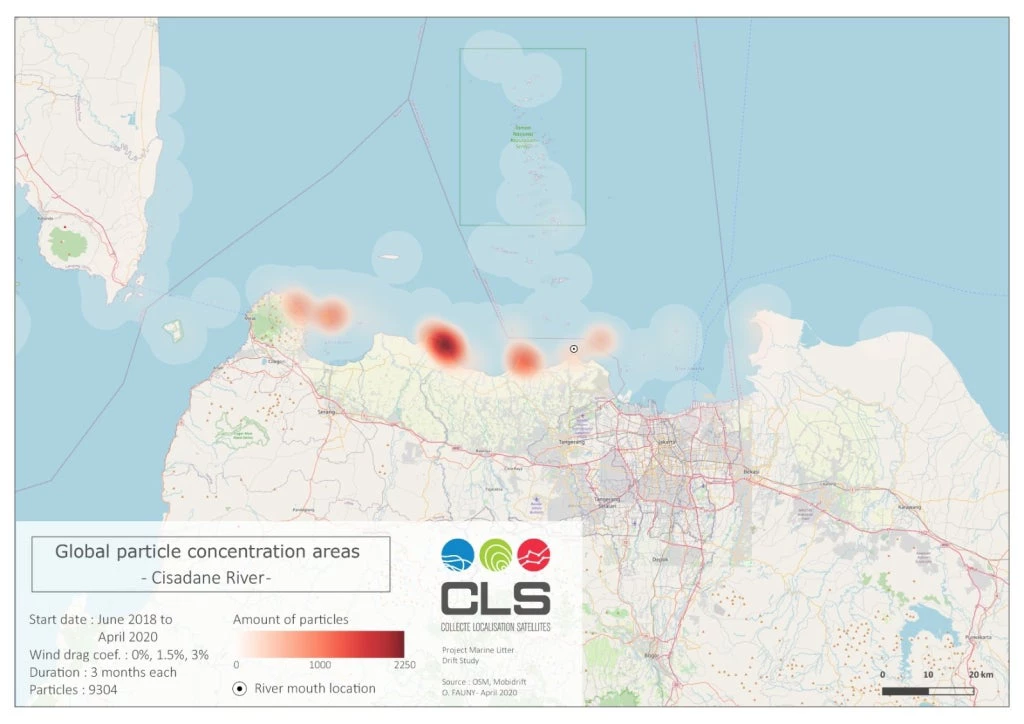

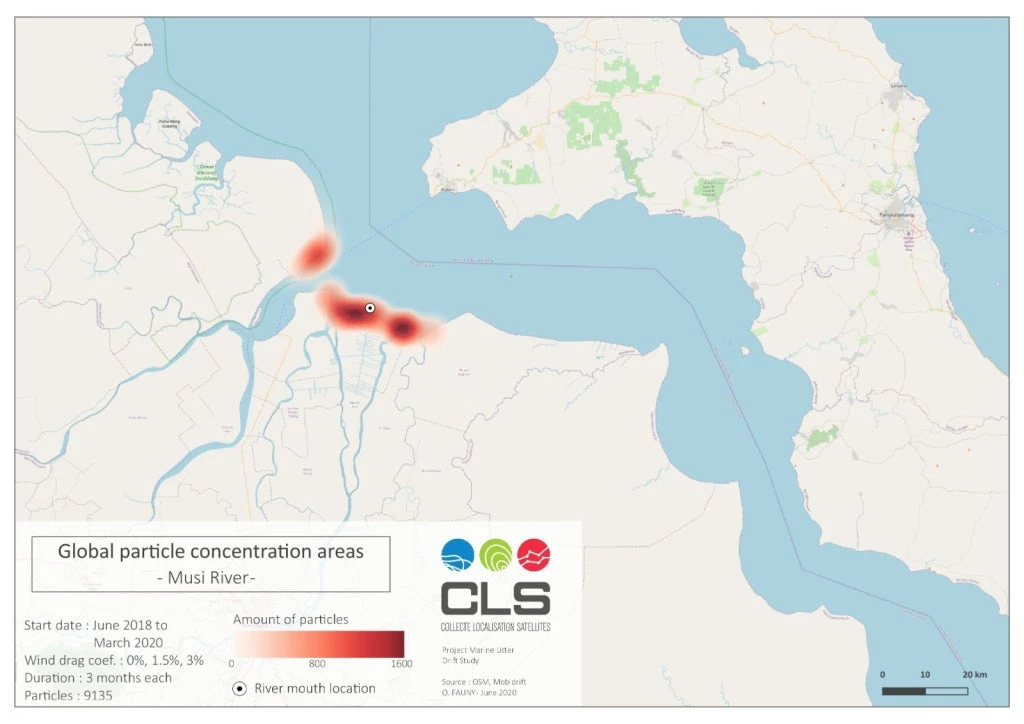

A study conducted between 2018 and 2020 tracked the final accumulation zones for plastic particles originating from Indonesia’s three major rivers known as plastic debris hotspots. In the Cisadane and Musi Rivers, 65 percent of plastics accumulate close to the river mouth. In contrast, 90 percent of the plastic waste particles coming from the Solo River are dispersed broadly in Indonesian marine waters or drift away further into the Indian Ocean (Figure 3).

Third, single-use plastics (SUP) are the predominant plastic items identified in major rivers and on beaches.

Using drones and artificial intelligence to detect and quantify marine plastic debris floating and/or washed ashore, our study found that at least half (47 to 65 percent) of plastic items along riverbanks comprise SUP items, such as cup lids, caps, and small plastic items.

Although the findings may not be nationally representative with a sample size of just three rivers (Cisadane, Citarum, and Bali), they support the argument that phasing out SUPs is likely to reduce the volume of plastics leaking to Indonesia’s marine environments. These findings are also consistent with other studies, including a national scale stranded macro-debris study that found that SUPs were the dominant microplastic debris in 18 beaches in Indonesia.

Finally, target single-use plastics through policies placing restrictions and fees on the use of SUPs, especially those with readily available alternatives. Restrictions and fees promote a phased approach to reducing plastic consumption without significant economic disruption. Together with the Indonesian National Plastic Action Partnership and CMMAI, the World Bank has prepared a roadmap of policy options to reduce plastic waste at source by (i) accelerating efforts toward zero SUP waste, (ii) adopting alternatives to SUPs, and (iii) increasing the efficiency of mechanisms enforcing the responsibility of producers for the waste they produce.

At the World Bank, we are committed to produce high-quality analysis to support and guide policy reforms, pool investments, and provide financing to support Indonesia in combating marine plastic pollution. We do this in Indonesia through support from the PROBLUE and the Oceans, Marine Debris and Coastal Resources Multi-Donor Trust Fund supported by Norway, Denmark and Canada. With various actions taking place in Indonesia, the fish and manta rays shown in the video can swim freely in a clean and clear blue ocean.

------------

The studies on marine debris in Indonesia were supported by the World Bank in collaboration with Poseidon/Hatfield, CLS-Indonesia, the German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence/Bandung Institute of Technology, and the Environment Agency Austria with Waste4Change. The World Bank’s work on marine plastics in Indonesia is supported by PROBLUE and Oceans, Marine Debris and Coastal Resources Multi-Donor Trust Fund funded by Norway, Denmark and Canada.

Read the World Bank report on ALDFG here and other studies on marine plastic here.

Join the Conversation