انځور: د رومي مشورتي شرکت

انځور: د رومي مشورتي شرکت

When I graduated from Balkh Medical University in 2004, there was no question in my mind what I would do next.

Aware of the poor condition of the national health system then, I immediately began working in primary health centers and clinics in remote areas in my home province of Balkh in northern Afghanistan.

As an ambitious new doctor, I quickly realized that good communication and coordination skills would be critical to providing the best care possible to local communities.

During the two years that I provided front-line health services in rural districts, I listened to the poor and vulnerable people our clinic served.

Most of them complained of their long journeys to our clinic, the unavailability of local transport, the lack of privacy at the health facility, and the limited capacity of the health facility to provide care.

Some of my patients would walk seven hours to reach the health facility. Women and children living in rural areas are among the most disadvantaged segments of the communities.

In many cases, they, especially women, sought treatment too late, when their health condition had already deteriorated.

When I asked why they had waited so long, they often answered that they had to wait for a maharam (a male companion—husband and/or in-laws) to accompany them to the health facility.

Some of my patients would walk seven hours to reach the health facility.

My experience taught me about the challenges these communities faced, mainly poor access to health services and the socio-cultural norms that kept women and children from using health services.

My patients' stories and ordeals still influence how I perform my job today as an advisor for the Sehatmandi Project at the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH).

In 2012, I joined the MoPH, where I felt my skills and experiences could be best used to improve healthcare for my fellow citizens.

From my time working in rural communities in Balkh, Sar-e-Pul, and Takhar Provinces, I find that working closely with the community is highly effective in overcoming local challenges.

I recall, when several households refused our immunization and maternal and health services outreach. Then, the community health shura (council) intervened and resolved the situation.

Similarly, on another occasion, the community health shura mobilized community resources to build a perimeter wall around the health facility to improve safety and privacy, particularly for women.

Based on my community-level experiences, I have concluded that local problems are best solved with local solutions.

I believe that, as a ministry, we cannot and should not sit at our desks in Kabul writing up solutions to issues in rural areas.

Instead, I believe that the ministry can best serve people by being active in communities, seeing the issues first-hand, and empowering local residents to find the best solution.

As such, I was especially pleased when the System Enhancement for Health Action in Transition (SEHAT) was announced in 2013 as it would focus on community-level efforts.

SEHAT was a core MoPH project from 2013 to mid-2018.

The project contributed to strengthening Afghanistan's healthcare and increasing access to critical health services through better facilities and services at the community level.

The improvement in national health care is reflected in current health status indicators.

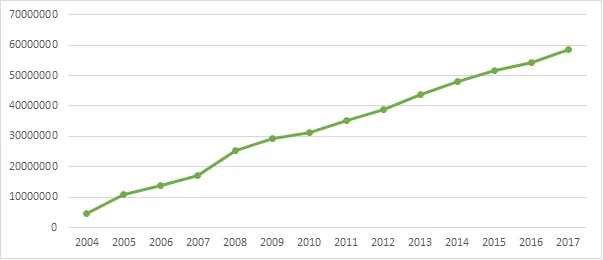

Figure 1. Number of and trend in patient visits to primary health care centers, 2004–2017

More than 87 percent of the population is within two hours of health care facilities by any transportation means.

Public hospital admissions have also seen a similar upward trend with an increase from 23,299 in 2004 to over 1.4 million in 2017 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of and trend in public hospital admissions, 2004–2017

The number of community midwives has increased from 467 in 2002 to over 4,000 today.

The significant progress in Afghanistan’s healthcare can be attributed to committed leadership, improved stewardship and governance, sound MoPH public health policies/ strategies, and the development assistance to the SEHAT program.

In July 2018, the Sehatmandi project succeeded SEHAT and will build on its efforts to expand the scope, quality, and coverage of health services in Afghanistan.

Sehatmandi project has been designed to engage communities in managing health services delivery .

SEHAT received support from the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF), administered by the World Bank on behalf of 34 donors, and the International Development Association (IDA), the World Bank Group’s fund for the poorest countries, in partnership with multiple donors.

Sehatmandi is supported by the ARTF, IDA, and Global Financing Facility, a multi-stakeholder partnership that prioritizes high impact but underinvested areas of health.

Join the Conversation