Photo: Rumi Consultancy / World Bank

Photo: Rumi Consultancy / World Bank

When the political crisis hit Afghanistan in August 2021, the private sector was already struggling with an unfavorable investment climate, political instability, endemic corruption, low business confidence, and underdeveloped market infrastructure. Businesses were barely recovering from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, including lockdowns and trade disruptions. The abrupt collapse of the government disrupted the functioning of institutions, threw the financial sector into crisis, and largely cut off the flow of foreign aid. The resulting economic shock interrupted the delivery of basic services and further compromised the private sector’s ability to help create jobs for the 600,000 people who are estimated to enter the labor market each year.

In parallel with the work undertaken through the Afghanistan Welfare Monitoring Survey to assess changes in basic living conditions in the wake of the political crisis, the World Bank conducted two surveys between October 2021 and June 2022 to better understand the impact of the series of shocks on the private sector.

More than three-quarters of businesses surveyed in the second round were operational, although most were working well below capacity.

The first round of the Private Sector Rapid Survey (PSRS) concluded that the crisis had a severe impact on businesses. At least a third of surveyed firms had shut down operations and a majority of firms engaged in widespread layoffs to cope with declining sales and new constraints , such as international sanctions and their implications for banking sector functionality and liquidity.

The second round survey showed some improvement, and that firms are finding ways to keep the lights on. For example, more than three-quarters of businesses surveyed in the second round were operational, although most were working well below capacity.

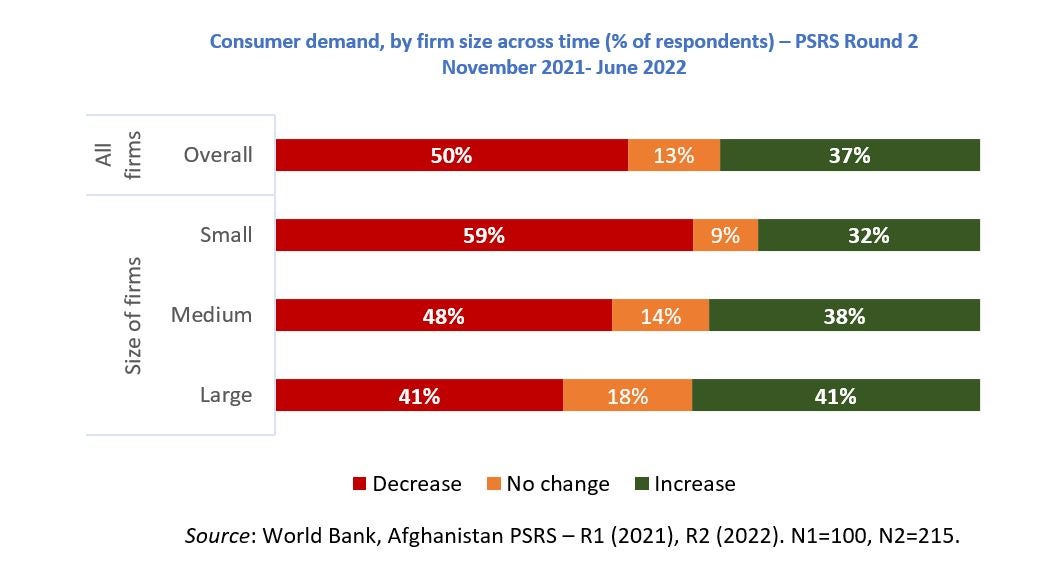

While businesses’ uncertainty about the future has subsided, the lack of consumer demand remains a problem. Still, consumer demand appears to have stabilized for at least half of surveyed firms in recent months. “Since I have been in agribusiness and dried fruit production for long enough, I could sustain my old customer line to maintain my business and have some income,” shared a business owner in Kabul through the survey.

Private sector jobs are beginning to bounce back slightly, although they remain at half of pre-August 2021 levels, on average. Some firms have maintained employment by cutting pay, as in the case of a wholesale and retail trade firm in Kabul, whose owner shared: “We decreased salaries for our remaining staff by 40 percent just to keep their employment. Two of our female employees are laid off, but we still pay 30 percent of their salaries to support them.”

This is not to say that Afghanistan is back to business as usual. Firms continue to face a tough environment, with depressed demand for their goods and difficulties accessing banking services, particularly cross-border payments.

Restrictions on the banking sector have forced businesses to use cash for domestic transactions and rely increasingly on traditional Hawala* networks for international transactions. However, firms that work more often with international firms cite a preference for formal banking due to anti-money laundering and combatting the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) risks associated with Hawala payments. Indeed, over one-third of firms participating in the PSRS indicated that demand for exports and imports had declined since November 2021. “We have stopped exports completely,” reported a wholesale and retail trade firm owner in Kabul, “because our clients in Europe don’t want to use Hawala and they cannot send money through banks.”

Amid these difficulties, firms welcome the cessation of active conflict and lower incidence of corruption. Fewer than 10 percent of surveyed firms reported having made unofficial payments since August 2021, compared to 82 percent before that. However, women-owned companies remain vulnerable given the security situation and the restrictions imposed on their social and economic activities. “Security is not good for women,” shared an agribusiness owner in Kabul, “We have laid off most of our female employees, as they were no longer allowed to work.”

The private sector in Afghanistan plays an important role in the country’s economy and could be a more significant driver of growth.

A way forward

The private sector in Afghanistan plays an important role in the country’s economy and could be a more significant driver of growth. It will be critical to restore central bank functions and resolve banking sector constraints, particularly with regard to thorny payment challenges. It is equally important to keep corruption at bay and address border challenges. On top of these reforms, Afghan businesses could benefit from three key actions to help de-risk and incentivize private investment that spurs job creation.

First, Afghan firms are now disconnected from the rest of the world and need to access markets for their products. Spurring connectivity may include facilitating exports to Afghanistan’s conventional export markets and strengthening logistics and transportation networks to boost physical access to markets. Restoring correspondent banking relationships is also essential, as it will facilitate the processing of international payments and improve exports.

Afghanistan’s international partners can help boost the private sector’s ability to keep the economy moving

Second, more than half of surveyed firms reported having approached the Interim Taliban Administration to discuss problems they were facing but did not achieve resolution. The international community can help by supporting chambers of commerce and other business associations to advocate on behalf of businesses in the country and by promoting a fruitful public-private dialogue to ensure that Afghan firms have a voice in defining policies that affect the business environment.

Third, Afghanistan’s international partners can help boost the private sector’s ability to keep the economy moving, create jobs, and stimulate domestic demand by revitalizing firms and the value chains in which they function. Moreover, while the Afghan business community has expressed gratitude for the humanitarian assistance donors have provided in the aftermath of the political crisis, they are pressing to make greater use of local businesses to support associated activities, such as logistics and handling. This would not only help to address immediate humanitarian needs, but also promote job creation, incomes, and demand over the longer term.

--------------------

*Hawala is an informal system to transfer funds from one geographic location to another and is used as an alternative remittance channel outside of traditional banking systems.

Join the Conversation