How to tackle vaccine hesitancy? Photo: Shutterstock

How to tackle vaccine hesitancy? Photo: Shutterstock

As the first COVID-19 vaccines started being administered a little more than a year ago, a wave of optimism swept a world battered by millions of deaths and facing an economic crisis due to the pandemic. While vaccines are one of the key interventions to reduce the severity of COVID-19 and help countries reopen their economies, a fundamental challenge has limited the impact of this major scientific advance: the hesitancy of millions to take the shot.

In January 2021 the World Bank launched a new program to support countries to understand and reduce vaccine hesitancy using behavioral science. The work is done through social media surveys and randomized experiments, allowing us to understand people’s beliefs about COVID-19 and vaccination intentions. A chatbot — a software application that simulates human conversation — facilitates conducting these surveys. The information is then used to inform the countries’ behavior-change communications to address vaccine hesitancy.

The work was initiated in the Middle East and North Africa region, with Iraq and Lebanon as the first two pilot countries. The program subsequently expanded to a total of 17 countries in 2021 (in all World Bank regions), and in three of these countries we deepened the engagement with multiple rounds of testing. In all, over 140,000 responses about COVID-19 vaccine intentions and behaviors have been collected through 24 social-media surveys in 11 languages. As we scale this work to more countries, and to mark the one-year milestone, 10 lessons in addressing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy globally emerge:

- Vaccine hesitancy is different from vaccine resistance. Vaccine hesitant individuals are unsure about getting the COVID vaccine and often have specific concerns that can be addressed with tailored messaging delivered by a trusted messenger. Those who are firmly against the vaccine are typically a much smaller proportion of the population than the undecided.

- Hesitancy and resistance are driven by a range of concerns and factors. Most unvaccinated people fall into one of three categories: (i) those with safety concerns specific to the COVID-19 vaccines; (ii) people with limited knowledge and information about the vaccines; and (iii) people who have low trust in institutions (either government or the pharmaceutical industry). The first two characteristics tend to be more common in vaccine hesitant individuals, while the last is a common belief among those who are against the vaccine.

- Vaccine hesitancy remains common across regions. While hesitancy rates vary by country and over time, on average one in three unvaccinated respondents is unsure about getting vaccinated.

- Safety concerns are driving most hesitancy. The most common concern among the unvaccinated is the perceived health risks of the vaccines (33% on average across all 17 countries). However, by now the evidence on vaccine safety is clear!

- Different types of concern call for different types of messaging. Sending personalized messages that speak to individuals’ specific vaccine concerns increased intention to vaccinate more than generic messaging. Multiple messages were tested and adapted, with targeted messages improving intent to get vaccinated by up to 80%, compared to the control non-targeted messages. As vaccine safety is the most common concern, messages about vaccine safety from a trusted source are a low-hanging fruit and could be integrated into all countries’ communication strategies to improve vaccination.

- Messaging should be modified as the pandemic evolves. The only constant is change. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to rapidly evolve, we update and test new messages to respond to concerns about emerging variants, vaccine efficacy against new variants, and vaccination of children.

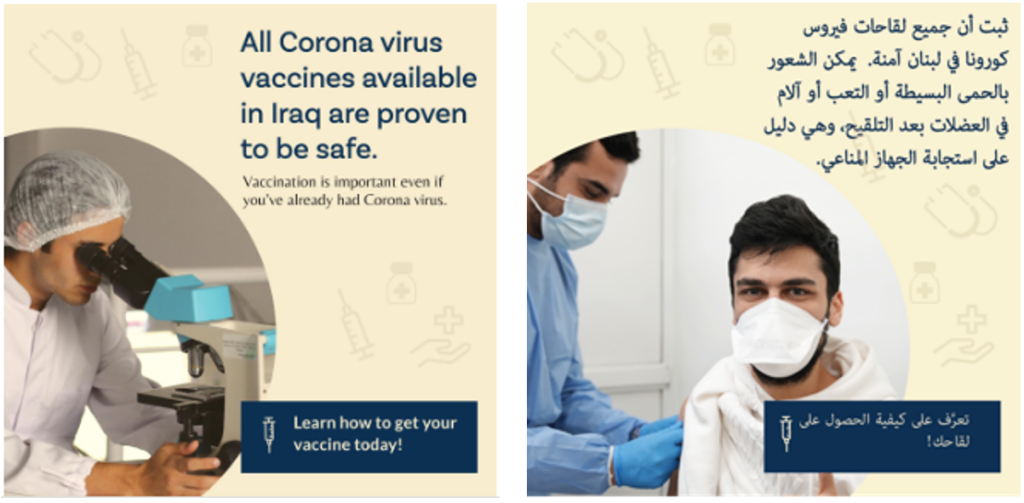

Figure 1: Example of behaviorally informed messages - Social norms are powerful. Across regions and countries, we find that people surround themselves with like-minded individuals. Vaccine belief of an individual is often aligned with the vaccine belief of the social network which the person belongs to.

- People trust certain messengers more than others: The most trusted messengers are healthcare workers and friends/family members (38% and 23% respectively among the 17 countries). While religiosity is high in many regions, religious leaders were only occasionally cited as a trusted source of vaccine information (3%). Within social networks with low vaccine intentions, identifying such messengers to communicate about vaccine benefits and address vaccine concerns can pay off.

- While health workers are highly trusted messengers, vaccine hesitancy among them is significant. Around 33% of health workers are vaccine hesitant, which tends to be in line with the level of vaccine hesitancy among the general population (37%). This presents a big challenge for vaccine communication efforts. Addressing hesitancy among health workers is critical.

- Country ownership is essential. Our most successful experiences, in terms of scaling this work, were in countries where local stakeholders were supportive and interested in learning from the initiative. Government partnerships and engagement with development partners on the ground such as the World Health Organization and UNICEF from the beginning of this initiative allowed us to have the most impact on COVID communication campaigns.

What’s next? During 2022 we will build upon these initial lessons to adapt and scale this work to support governments in their communication about the COVID-19 vaccine. To build country capacity and adapt to local context, we will deepen these engagements to focus on emerging themes such as healthcare worker hesitancy, exposure to misinformation, youth hesitancy, and beliefs about new variants. Capacity of governments to adapt their communication strategies using our results varies by country and depends on capabilities, capacities, and bandwidth. Addressing explicitly country-specific needs is therefore required. In addition, we are making efforts to adapt the diagnostic tool to different country contexts and phases of the vaccine rollout, for example by finding new data-collection solutions in regions with low internet access (such as using other platforms like WhatsApp), specifically relevant in Africa where use of social media platforms like Facebook is less common. Finally, the need to target various demographic groups will require different approaches to reach people (for example TikTok and Instagram for youth) and partnerships with civil society organizations to reach older populations and health workers directly.

The work, led by the Mind, Behavior, and Development (eMBeD) unit among other World Bank units, is supported in part by the Alliance for Advancing Health Online (AAHO), an initiative to advance public understanding of how social media and behavioral sciences can be leveraged to improve the health of communities around the world. Countries/territories where the program took place: Cameroon, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Honduras, Iraq, Jordan, Kosovo, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, North Macedonia, Papua New Guinea, Saudi Arabia, Serbia, Tunisia, West Bank and Gaza

For additional information, please contact embed@worldbank.org.

Join the Conversation