Addressing gender inequality in pension systems requires a multi-faceted approach. Copyright: Shutterstock

Addressing gender inequality in pension systems requires a multi-faceted approach. Copyright: Shutterstock

Despite recent attention in the media, progress in closing the gender pension gap in most countries has halted. These sources point to a stark disparity in retirement outcomes, with women receiving pensions that are between 25% to 30% lower than those of men. Methodological differences to estimate the gap don’t make it less striking and are no excuse for inaction.

Why does the gender pension gap exist?

The biggest driver of the gap stems from the fact that women are less likely to be in wage employment or work full-time in formal and informal labor markets. They are also more likely to earn lower wages when they do. Unpaid care work and household chores limit their potential access to economic opportunities and result in more frequent and longer breaks in employment, reducing pension contributions and accrual of benefits.

Implementing adequately long and paid parental leave, can improve their employment outcomes. According to World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law, the most persistent gender gaps are in the laws pertaining to women’s employment during pregnancy and after having children. Evidence from Mexico and Uruguay show that earnings-related contributory pensions are closely tied to the socio-economic circumstances experienced during active years. The pension gap is fully intertwined with the gender pay gap, the motherhood pay gap, and the jobs gap.

How to address the gap

Addressing gender inequality in pension systems requires a multi-faceted approach, including pay equity, reducing constrains to access economic opportunities for women, and addressing social norms. Absent progress in those structural challenges, gender-informed pension systems reform can help reduce this gap. Pension systems can be adjusted with equal retirement ages for men and women, reduced vesting periods for women, greater redistribution within the pension system, wider coverage through non-contributory pensions, automatic indexation of pensions to inflation, and better designed survivor pensions:

- Equal retirement age:A lower retirement age for women reduces the number of years women work and contribute to the pension system and consequently their retirement benefits. Furthermore, it may also impede women’s training opportunities, career growth and equal access to higher-ranking positions with better pay. While the trend over the last two decades has decisively been towards eliminating retirement age differentials, 63 (out of 190) countries continue to have lower retirement ages for women; in 2020 that figure was 92. Often the differential is maintained due to the inaccurate perception that lower retirement age is a benefit to women. Achieving retirement age parity between genders may require not only writing equal retirement ages in the law but also a change in the public perception that an equal retirement age is unfair and discriminatory towards women.

- Fewer minimum years of service required for women to qualify for a pension: Long minimum vesting requirements to qualify for a pension implies that many women fail to meet minimum eligibility conditions, resulting in lower pension coverage. Longer vesting periods may also create disincentives to enroll in mandatory contributory schemes, especially in economies with high concentrations of women in informal work. Longer minimum vesting periods disproportionately disadvantage women and result in fewer women earning a pension in their own name. In cases where retirement ages for women are lower, vesting periods are generally also expected to be lower, but this is not the case in at least 19 countries.

- Progressive redistribution of pension systems: Pension systems have different modalities including social assistance benefits, separate targeted retirement-income programs paying a higher benefit to poorer pensioners and reduced benefits to better-off retirees, basic pension programs, and minimum pensions within earnings-related plans. Low benefit levels and coverage can be mitigated by either non-contributory pensions or by redistribution in the pension formula in defined benefit plans. Evidence from Chile shows that non-contributory pensions narrow the gender gap that comes from the contributory pension system by half. Non-contributory pensions are the favored approach, especially in low- and middle-income countries since most of the elderly need financial support are outside the contributory pension system.

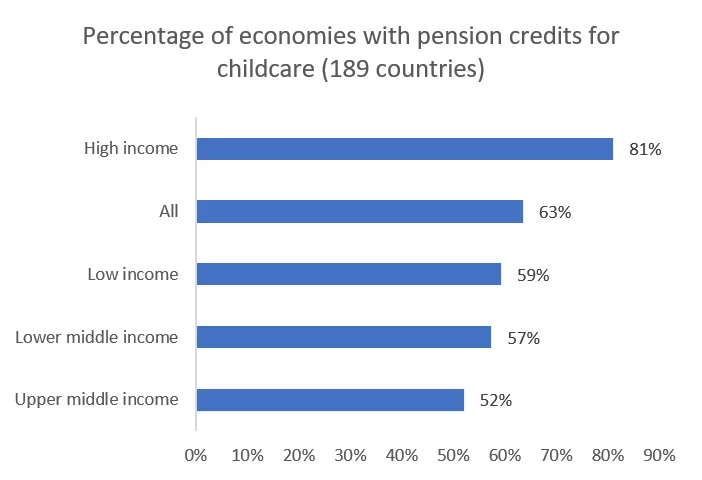

- Compute extra years for breaks in employment due to care responsibilities. Taking time off work to care for children or the elderly reduces career length, contribution records, and wages, leading to lower pension benefits for women. In 2021, almost all the 185 countries surveyed by the ILO have adopted statutory provisions for maternity leave in their legislation. However, periods of maternity leave are not always recognized as employment for pension computation purposes. Overall, among the 190 countries examined in this study, childcare-related absences are accounted for in pension benefits in only 107 countries.

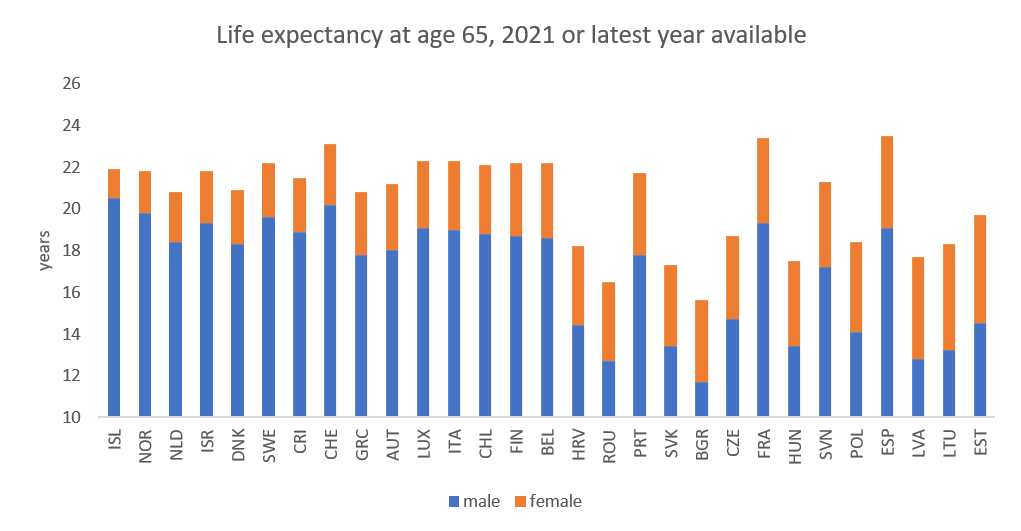

- Adjustments for inflation: Since women’s duration of retirement tends to be longer—both because of lower retirement ages and longer life expectancies—they are more vulnerable to poverty in old age if pensions aren’t adequately indexed to inflation. While most OECD economies index pensions at least to inflation, many developing countries apply discretionary increases – often dependent on budget availability. Inflation indexation constitutes best practice as it aims to maintain the purchasing power of pensions in payment.

- Improve design of pension benefits.Survivor pensions can help offset consequences of the array of inequities women face during their active years. Their objective is to compensate for men’s higher participation in formal wage employment and wider pension coverage. Countries typically provide at least some form of survivor benefits. Periodic survivor pension levels typically amount to a fraction of the deceased’s pension amount. However, some countries provide only lump-sum survivor benefits, which can fail to adequately protect widows from old-age poverty in later years.Best practice informs the ideal design of survivor pensions is in the form of a lifetime annuity pension, indexed to inflation.

Reducing gender gaps in pension systems requires comprehensive and integrated policies and action with Ministries of Labor, Finance, and Social Welfare working together alongside social security and pension authorities, private sector financial institutions, civil society organizations, and international organizations and academia. It is not only the right thing to do, but also an economic imperative.

The World Bank’s Pensions and Social Insurance Global Solutions Group, a joint team of both the Social Protection & Jobs and the Finance & Markets Global Practice, is focused on analysis and reform of pension schemes around the world, including supporting countries in addressing the gender pension gap through technical assistance and country-specific projects. The World Bank’s ASPIRE database has been recently expanded to include gender disaggregated data on performance statistics of contributory pension programs, which further facilitates the organization’s ability to advocate for evidence-based pension policy formulation that contributes to closing the gender pension gap.

Join the Conversation