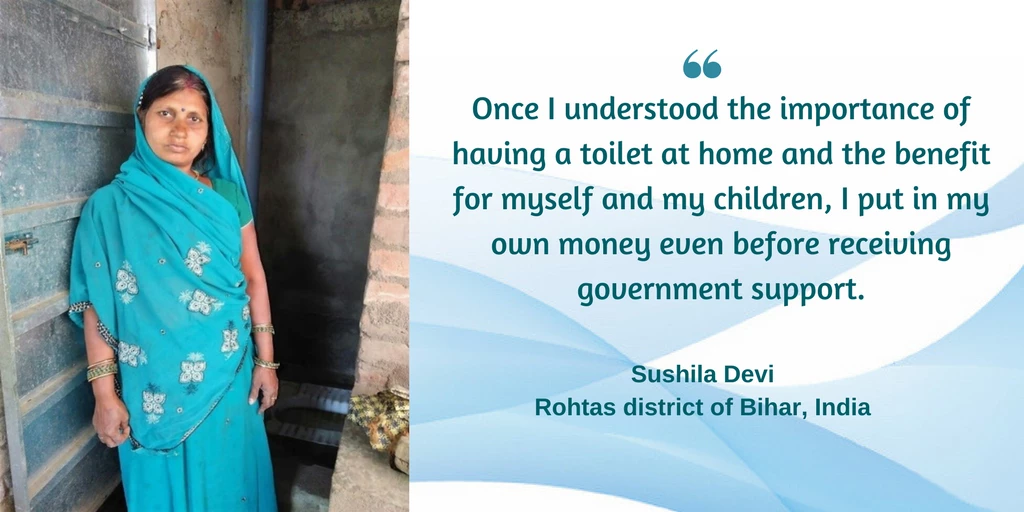

Sushila Devi, a mother of four in the rural Rohtas district of Bihar, India, has no significant assets and depends primarily on casual labor for income. She recently was able to take out a bank loan of INR 12,000 (US$180), which she used to construct a toilet in her family home

It was the Self-Help Group (SHG) in her village that persuaded Sushila of the importance of sanitation for her children’s health and nutrition, and helped her get the loan she needed. SHGs generally consist of 12 to 15 rural women, grouped into larger federations. They engage with formal financial institutions to help unbanked households access financial services, acting as platforms for standardized large-scale sensitization of community members on a variety of subjects.

Sushila’s actions are part of a larger change driven across Bihar by the recently launched Bihar Transformative Development Project (BTDP), commonly known as JEEViKA-II. This joint initiative of the Government of Bihar and the World Bank covers 300 (56 percent) of the blocks of rural Bihar. The project is working through SHGs to deliver awareness, training, finance, and monitoring on sanitation and nutrition in an integrated manner.

Bihar is a challenging terrain. It has the highest rural population density in India and a per capita income barely half of the national average. A third of its population lives below the poverty line, and more than two-thirds of rural households do not have access to individual toilets. Only seven percent of children between six months and two years receive an adequate diet both in terms of diversity of nutrients and quantity — dictated more by lack of knowledge than resources. With a growing body of research linking open defecation to disease and child malnutrition, it is not surprising that the prevalence of stunting in children under the age of five in Bihar is a staggering 49 percent, much higher than the national average of 38 percent.

The Bihar Transformative Development Projects is using SHGs to address these issues and reach women at an unprecedented scale. The project’s integrated approach reflects lessons learned internationally, in fields such as rural sanitation, nutrition, and rural livelihoods. It involves collaboration among a number of departments within the World Bank, including the Water Global Practice, the Agriculture Global Practice, and Health, Nutrition, and Population Global Practice — each bringing lessons learned from their respective disciplines.

The approach has been tested in varied settings, and detailed guidelines and toolkits are now being drawn up. Project staff is trained to scale up this initiative across Bihar, and the lessons learnt, guidelines, and toolkits are used to scale up across rural livelihood projects in other states, such as Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and Maharashtra.

Scaling up involves several steps. First, a comprehensive package of behavior change communications on sanitation and nutrition practices is delivered across a village. Working through SHGs makes mobilization and communication easier, as they hold regular weekly meetings where trained female community mobilizers can deliver a uniform set of messages repeatedly across the community.

When this triggers demand for better sanitation among SHG members, such as Sushila, the SHG’s federation is able to provide them with ready options for financing the construction of a toilet, as well as to help them see if they are eligible for benefits from government programs such as Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM). Importantly, these links with finance providers reduce the gap from mere orientation to taking immediate action. Similarly, an understanding of the benefits of diet diversity on maternal and child health is supported by resources and training to grow nutrient-rich vegetables in backyard kitchen gardens.

By design, the project works exclusively with women. Membership of SHGs empowers women by enhancing their economic contribution to their households , thereby giving them a greater say in household decisions.

The project’s design also addresses the common problem that a new toilet doesn’t always translate into active usage or sustained behavior change. Village federations lead post-construction monitoring through regular visits to these households, while messages around the health linkages between nutrition, hygiene, and sanitation continue to be delivered through SHGs. Capacity-building and peer support help women adopt hygienic practices and improve dietary habits.

For Sushila Devi, in addition to constructing a toilet, she also grew a vegetable garden in her backyard; a good example of improving her diet that the project will use to try to persuade more than five million rural poor households in Bihar to follow.

Join the Conversation