Bandung, Indonesia—Slums on the banks of the Cikapundung River in Bandung. | © shutterstock.com

Bandung, Indonesia—Slums on the banks of the Cikapundung River in Bandung. | © shutterstock.com

For centuries, cities have provided refuge to millions fleeing wars, famines, and other shocks. But cities themselves are vulnerable to shocks—from overcrowding, disease, violence, and social unrest. How well are cities in developing countries doing as shock absorbers? We examine these questions in our new report, Vibrant Cities.

The 2020s have been an era of shocks: COVID-19, inflation, climate change, and social unrest are merely the most prominent among them. In developing countries, cities have not been effective shock absorbers. Consider four strands of evidence:

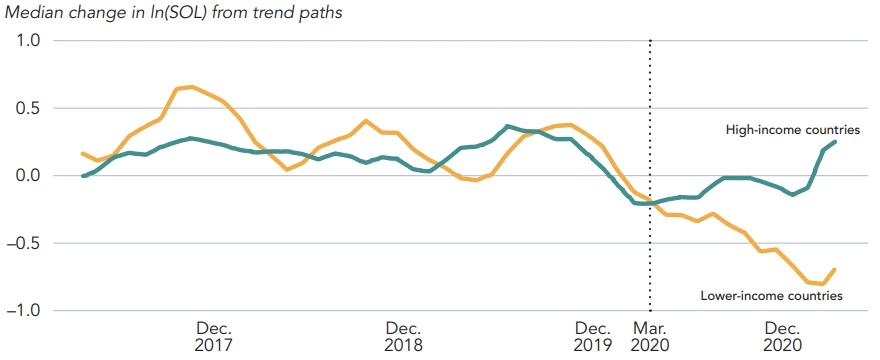

- COVID-19’s economic impacts were worse in these cities: The disease and countermeasures to contain it both hurt urban economic activity everywhere. Yet cities in developing countries suffered deeper economic contractions and slower recovery than cities in developed countries.

Figure 1: Cities in developing countries were hit harder by COVID-19

Source: Khan et al. 2022.

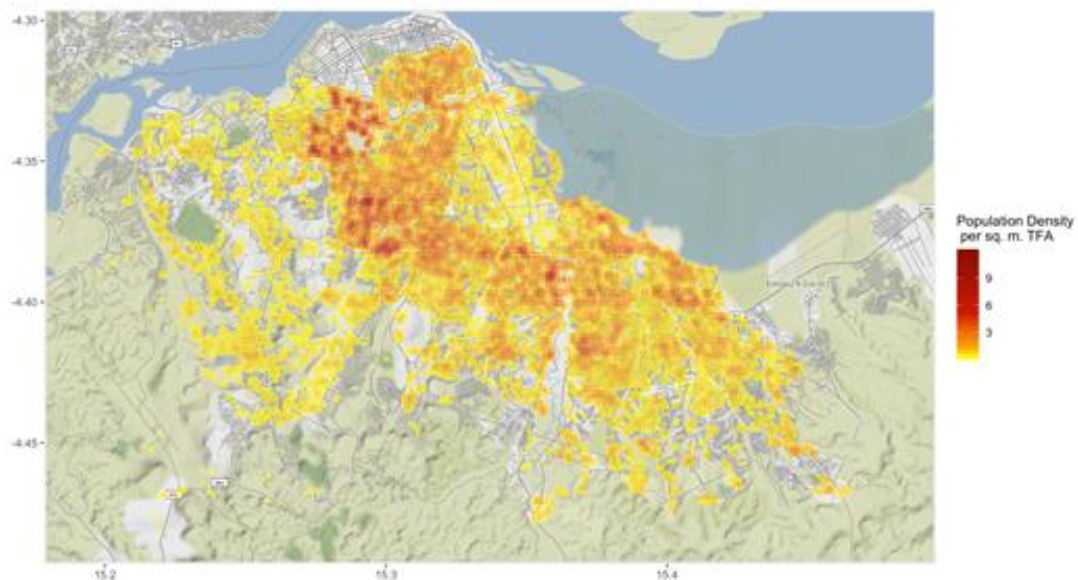

- Overcrowding exacerbated COVID-19’s contagion risks. More than 35 percent of the urban population of developing countries live in slums. Overcrowding, in short, is a feature of many cities in these countries. People live in substandard housing, lack open space, and have inadequate infrastructure. During the pandemic, most people simply did not have the capacity to socially distance themselves, leading to “contagion hotspots” (figure 2).

Figure 2: Overcrowding exacerbated COVID-19 hotspots in Kinshasa

Note: the color represents the intensity of the hotspot from low intensity (yellow) to high intensity (red), but all hotspots are already in high-risk locations

Source: Lall and Wahba 2021.

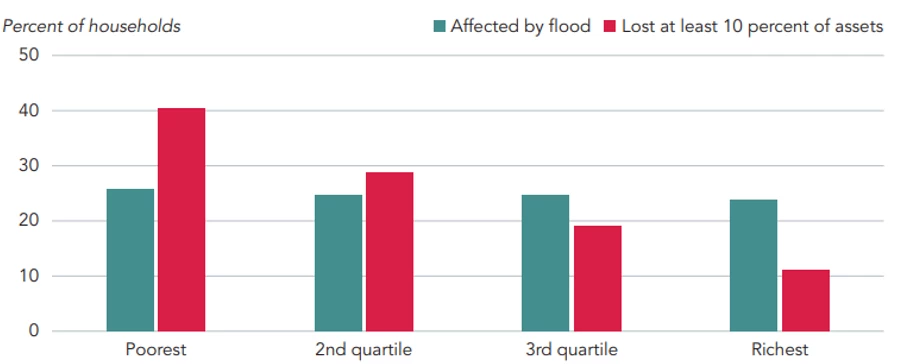

- Mother Nature’s punches hits cities in developing countries harder: Floods impede economic activity, and the effect is greater in cities in developing countries—with night lights (a proxy for economic activity) falling by 8.3 percent compared with just 1.4 percent in high-income countries. In Jordan’s capital, Amman, more than half of the at-risk households are low-income with low capacity to cope with floods. About 66,900 of Amman’s households are potentially exposed to pluvial flooding, including 34,300 low-income households. In Accra, flooding causes heavy asset losses for a large share of poor households, even though the probability of flooding for such households is no greater than it is for non-poor households. (figure 3).

Figure 3: Flooding in Accra leads to heavy asset losses for a large share of poor households

Source: Erman et al. 2018.

- Economic benefits are captured by elites and insiders. In 14 slums in Bangalore, India, investing in children’s education was the top priority for households, and slum children tend to be better educated than their parents. In Jakarta’s slums, educational attainment has improved. Yet better education does not mean greater occupational mobility in either India or Indonesia. Most slum residents—particularly women—work in slums. They cannot secure more formal, high-paying jobs because they don’t have access to better job networks and are often isolated from city centers. Slum residents also face substantial downward mobility if they get ill or face other shocks.

What can such cities do to become better at absorbing shocks? Many policies have been recommended over the years—establishing formal land and labor markets, connecting neighborhoods efficiently, providing basic services more equitably, and so on. Some of these policies are technically hard or costly, but others are less so. Yet too many developing country cities fail to make even basic reforms and investments. Why?

In Vibrant Cities, we examined how trust and legitimacy—what citizens expect of their public servants, and vice versa—shape social contracts. Without legitimacy, compliance with regulations is low. It requires more costly—often infeasible—enforcement, making reforms largely ineffectual. Without trust, citizens are more likely to pursue actions that deliver individual benefits at the expense of society as a whole—such as extracting bribes, shirking public duties, dumping waste illegally, encroaching on land, and so on.

In Ceara, Brazil, the city took the opportunity of competitive municipal elections to provide better health services. Governors with reformist programs established a new cadre of public-health workers, who greatly improved the state’s health outcomes. They flooded news media with information about the value of public health and the role of the new cadre, creating public expectations and demands of public officials. This helped cement (and reward) elected officials’ commitment to the reform and instilled public health workers with a sense of professionalism driven by peer pressure to perform.

Cities also need to strengthen their fiscal capacity to fund their investment and reform programs. A distinguishing feature of urban policymaking is the sheer scale of the financing needed for urban infrastructure, adding long-term operating costs to initial capital outlays. In Morocco, the city of Casablanca successfully used delegated service providers to modernize management practices, enhance the quality of municipal services, and increase investment in urban infrastructure and services, contributing to the city's overall vibrancy.

Cities’ own fiscal capacity will remain limited as long as social contracts between city governments and citizens are weak. City leaders know they have at least three ways to mobilize the financing necessary for infrastructure and services—by taxing the value of land and property, forming private–public partnerships, and raising funds from the capital markets. The main obstacle is governance: City authorities will need to implement measures to enhance legitimacy and trust.

Cities in developing countries can become better shock absorbers for their residents—in much the same way as cities in developed countries have become. The process might be arduous, but it can be done. Now is as good a time as any to start.

Join the Conversation