Also available in: Русский | Română | Türkçe

Did you know that, in 1755, Portugal suffered a catastrophic disaster so severe that it cast a long shadow over politics, religion, philosophy, and science?

During an All Saints’ Day mass in Lisbon in that fateful year, an 8.5-magnitude earthquake collapsed cathedrals, triggered a 20-foot tsunami, and sparked devastating fires that destroyed nearly 70% of the city’s 23,000 buildings.

The death toll was estimated between 10,000-50,000, leaving the center of a global empire in ruins, with losses equivalent to 32%-48% of Portugal's GDP at the time.

Never in the European history had a natural disaster received such international attention.

The “Great Lisbon Earthquake” had a resounding impact across Europe: Depictions of the earthquake in art and literature – the equivalent of today’s mass media – were reproduced for centuries and across several countries. Rousseau, influenced by the devastation, argued against large and dense cities in the wake of the disaster, while Immanuel Kant published three separate texts on the disaster, becoming one of the first thinkers to attempt to explain earthquakes by natural, rather than supernatural, causes.

In the years to follow, careful studies of the event would give rise to modern seismology.

The reconstruction of the city was centered on decisive, ground-breaking measures:

- Science-driven reconstruction. Innovative engineering methods were used by employing a "caging" method by placing a flexible wooden structure in the walls of buildings that would “shake but not fall.” Other anti-seismic design features were tested by having troops march around them to simulate tremors, leading to the birth of earthquake engineering.

- Recovery planning to identify further risks. Marquis of Pombal, who led the reconstruction, was also mindful of how fatalities could be minimized in the future with good design. Large spaces, good ventilation, orthogonal streets – absent in the medieval city – were implemented to support evacuation and fire-fighting efforts.

- Leveraging co-benefits. Given the urgency and shortage of materials, blocks from collapsed buildings were used to create new pavements, allowing the city to recover much faster while transforming mass debris into modern streets.

(Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The large time interval between devastating earthquakes often explains why such risks quickly fall from collective memory. Historic earthquakes provide a snapshot of possible devastation from a major event. But if we add modern transport, electricity, water and communication lifelines, ageing apartment buildings, and more importantly, dense settlements, a more disturbing scenario emerges.

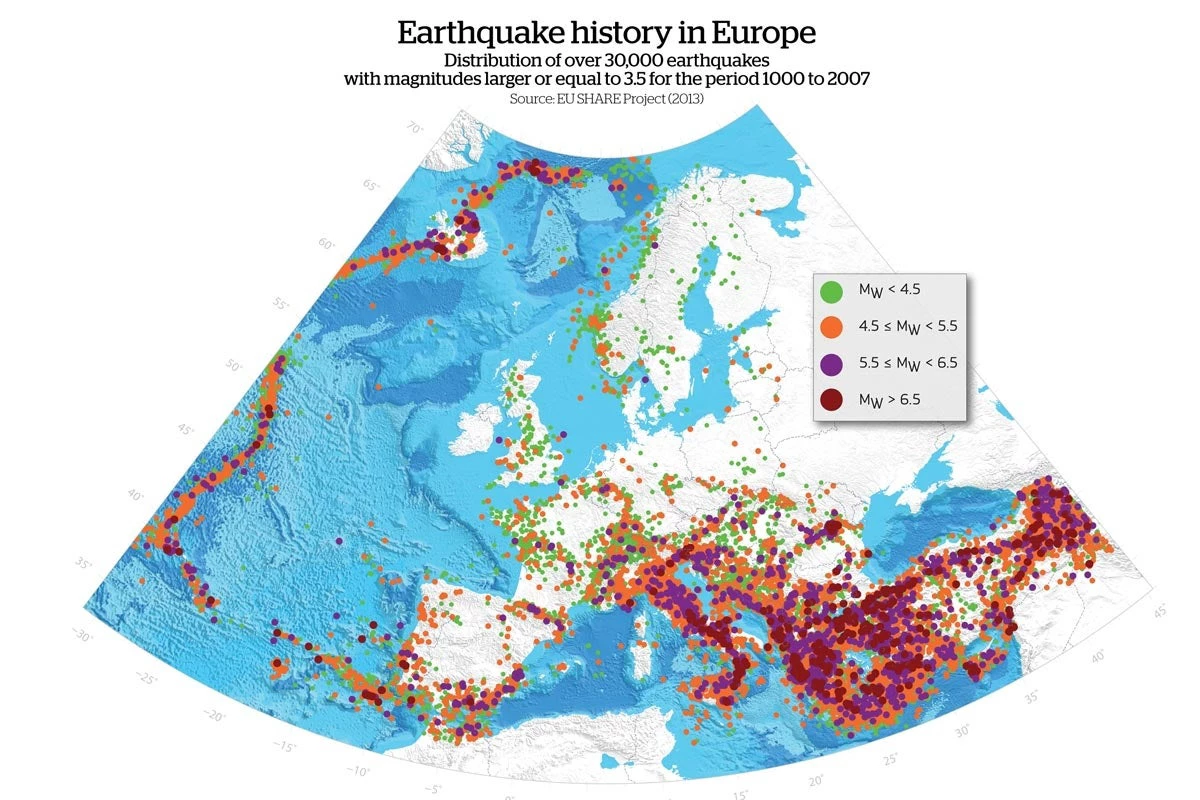

Experts can’t predict with exact precision when the next large earthquake will happen, but with the improvement of worldwide datasets in past decades, they all agree that the next big one is inevitable in seismic-prone countries, such as those in the Europe and Central Asia region. A recent report developed with support from the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery ( GFDRR) confirmed that Romania, for example, has the highest seismic risks in the EU: the country experiences two magnitude 7 or higher earthquakes every century.

Risk information like this does influence decision makers across Europe and Central Asia, who are working to build resilience alongside other forward-thinking measures, including energy-efficient investments .

In Istanbul, more than 1077 schools, 18 hospitals, 61 polyclinics and 114 public buildings are now protected from the next earthquake. Across Turkey, the Ministry of Education is taking critical steps to improve the seismic safety of its schools, without forgetting Syrian displaced children.

In Armenia, upgrades to the building code will follow investment and commitment in new analysis of the seismic risk.

In Bulgaria, concerns raised about seismic safety of apartment buildings are being thoroughly investigated.

And in Serbia, the government is pursuing policy and legislative reform to embed disaster resilience in government investments and maximize financial resilience in the aftermath of disaster.

While Lisbon was presciently rebuilt with sound Disaster Risk Management practices, important lessons from history have too often gone unheeded in today’s cities around the world. We must urgently accelerate our efforts to build resilience and prevent citizens from facing the devastation seen in Bucharest (1977), or exactly 350 years ago, in Dubrovnik (1667) or in Shamakhi (1667), and beyond.

It’s never too late to learn from history, to unlock stimulating knowledge-exchange opportunities, and remember why large earthquakes from the past undoubtedly matter for shaping today’s resilient cities.

Related links:

- Learn more about our work on building sustainable communities

- Subscribe to our Sustainable Communities newsletter and Flipboard magazine

- Follow @WBG_Cities on Twitter

Join the Conversation