Last December, James Dooley Sullivan packed his wheelchair and travelled to Jamaica. Sullivan, an animator and visual arts video editor at the World Bank Group, wanted to see first-hand what it’s like to be disabled in a developing country. He shares his experience and his own history in a video and a series of blog posts.

I shudder every time I think about the external force created when I hit the tree and how that force coursed through my snowboard and up my left leg, which shattered, and on up into my spine, which broke in two. It lasted only a second, but I will never stop thinking about that pressure. Now, I have a new pressure to think about: Pressure Sore.

Imagine it. I’m back from Jamaica and eager to create a film that will document my adventures, my thoughts and the lives of the people I met there. Instead, I’m lying horizontal and thinking, a lot of time thinking, about pressure.

Anyone can get a pressure sore, but the disabled are particularly vulnerable. As bone presses against flesh, the body protests. You shift your position without really thinking about it. Relief. But, I have to do this manually by performing a maneuver which is akin to popping up and down like a wack-a-mole in an amusement park arcade, except no one actually hits me with a rubber mallet. Every ten minutes or so, I have to lift myself up off of my butt and lean from one side to another so my pelvis has a break.

One night, after I got back from Kingston, my sheets bunched underneath me and I noted some reddening during my daily skin scan. I wasn’t too concerned because my skin usually recovers. Besides, I was preoccupied with the pressure to get my film done, and financial pressure to get to work as well.

There’s that word again. Pressure. The pressure to try and keep up with work and living a normal social existence and not appearing to be a weak crippled being. For the first time I was working on telling a story that I really cared about, and I was not ready to allow my passion, my progress, my responsibility to the people I met in Jamaica, to be waylaid by some damaged skin.

I understand that everyone suffers from all sorts of pressure but I would argue that people with disabilities experience it more intensely, because we are not normal. Every time I leave my house I put on an invisible layer of camouflage that is full of self-confidence, oozing with independence and strength. I propel my wheelchair, moving quickly and manipulating doors so as not to attract extra door-holding attention. Underneath however is a much more fragile being that requires an extra push up hills, for heavy doors to be opened, and to be bounced up and down despised stairs. My gender has given me the physical strength to push through almost any plush carpet that’s in my path. But, at the end of 2016, the mental and physical pressures that keeps me going came to a screeching halt.

The pressure I put on myself had to stop. I had to heal. I had no choice. It would be months before I could be in an edit suite again and work.

By the time I got back to working on my film about my experiences in Jamaica with Patrick Rodin, I knew the story I wanted to tell. I just wish I had unlimited time to tell it. I had to remind myself about every five minutes that it’s impossible to cram everything Patrick and I have to say into one 10-minute story. But, I wanted for sure to show what is possible - given enough time, love, and attention - in two very different countries.

Patrick, in his Jamaican cadence, can say better than I can what it’s like to find yourself in a wheelchair. "When you go and don’t see anyone like yourself, the brain’s kind of wondering, if I’m alone. When you see someone else in a chair approaching, I’m not alone." Patrick and I are part of what is now a global disabled community that is becoming increasingly connected. Together, we are finding each other on the internet and finding our voice, bit by bit, one vlogger and forum member at a time. For my money, it’s going to be epic, transformative, and inspiring as it unfolds across the globe. A good pandemic that heals instead of destroys.

Patrick is refurbishing a van that’s going to be a wondrous sight. “So this vehicle could take 5 of us sitting in their own wheelchairs,” he explains. “It’s very good, I love it. And I love the action of 5 or 6 of us who uses wheelchair going to one place and having everyone coming out.”

Piling into a van for a run to the grocery store may not seem like a revolutionary act. But for Patrick and his friends, it’s all about the idea of being seen, noticed, accounted for. Many impoverished disabled people live in rural areas, where there’s no accessibility, or stay shut in their homes, defeated. They are out of sight and out of mind. When Jamaicans turn their heads and see the disabled moving through their world, they will understand the need to make changes in the physical landscape. Patrick is a community leader and mentor first, and a mechanic second.

And I see myself differently as well. I am an editor and animator to earn a living. But now I’m also an educator. I can use my platform at the World Bank to tell the stories of people like Patrick. I can get them seen. Noticed. Accounted for. I want to be the catalyst that changes not just people’s perceptions, but laws as well. As an unknown filmmaker who refuses to go to law school, that is a pretty bold ask. I hope it transmits just how much this experience has changed me.

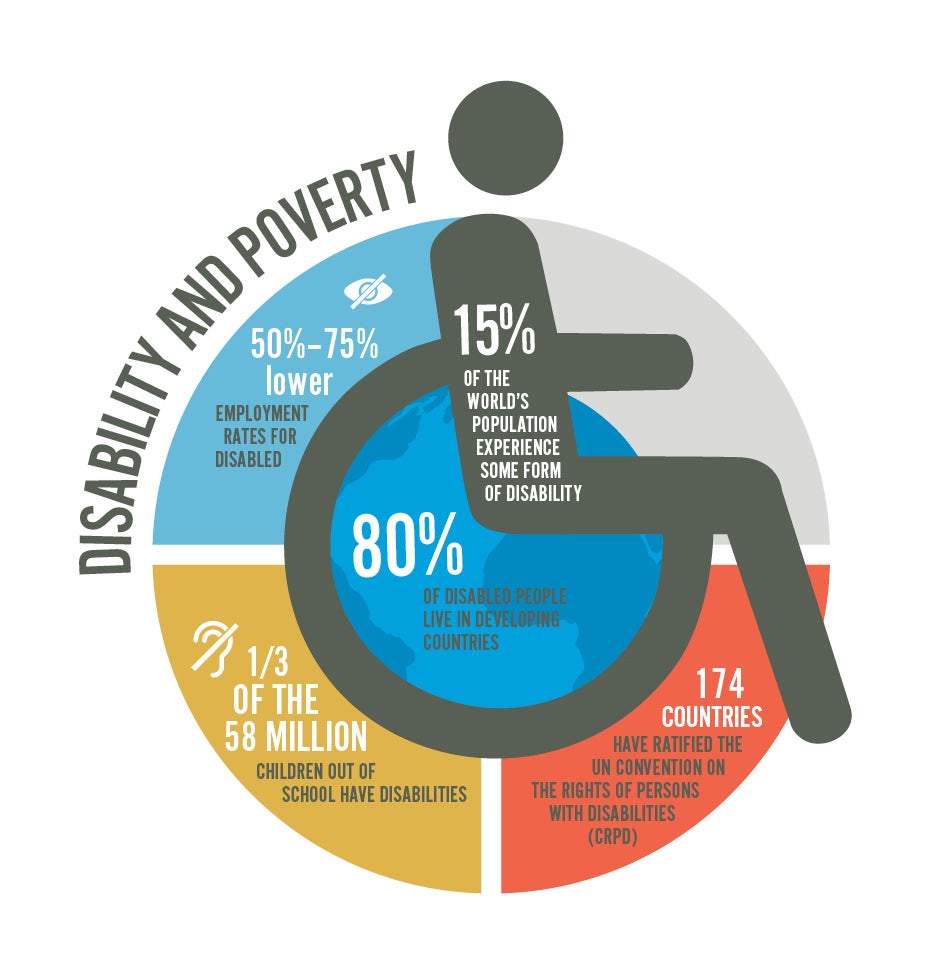

When my film was finally completed, I was asked to travel to New York and screen it at the COSP10 at the United Nations, an international meeting on the Convention for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). The iconic UN building was full of representatives of countries like Jamaica that have committed to improving access for all disabled citizens. Many of the attendees were like me, in wheelchairs, or they were blind, deaf or otherwise disabled. I was with my community.

When my film ended and the lights came up, one of the delegates asked if I would come to Africa to do a story about disability in his country. Another delegate asked if I could please do a story about the impoverished disabled who are confined to their homes. One group even wanted a photo op, surrounding me and my chair with big grins for the camera. This is energizing me to focus on telling more stories about what, only a few decades away, will be the new normal for millions of disabled people around the globe. You will be hearing from us.

Related links

- Report: Inclusion Matters: The Foundation of Shared Prosperity

- Brief: Disability

- Brief: Social Inclusion

- Topic: Social Development

Join the Conversation